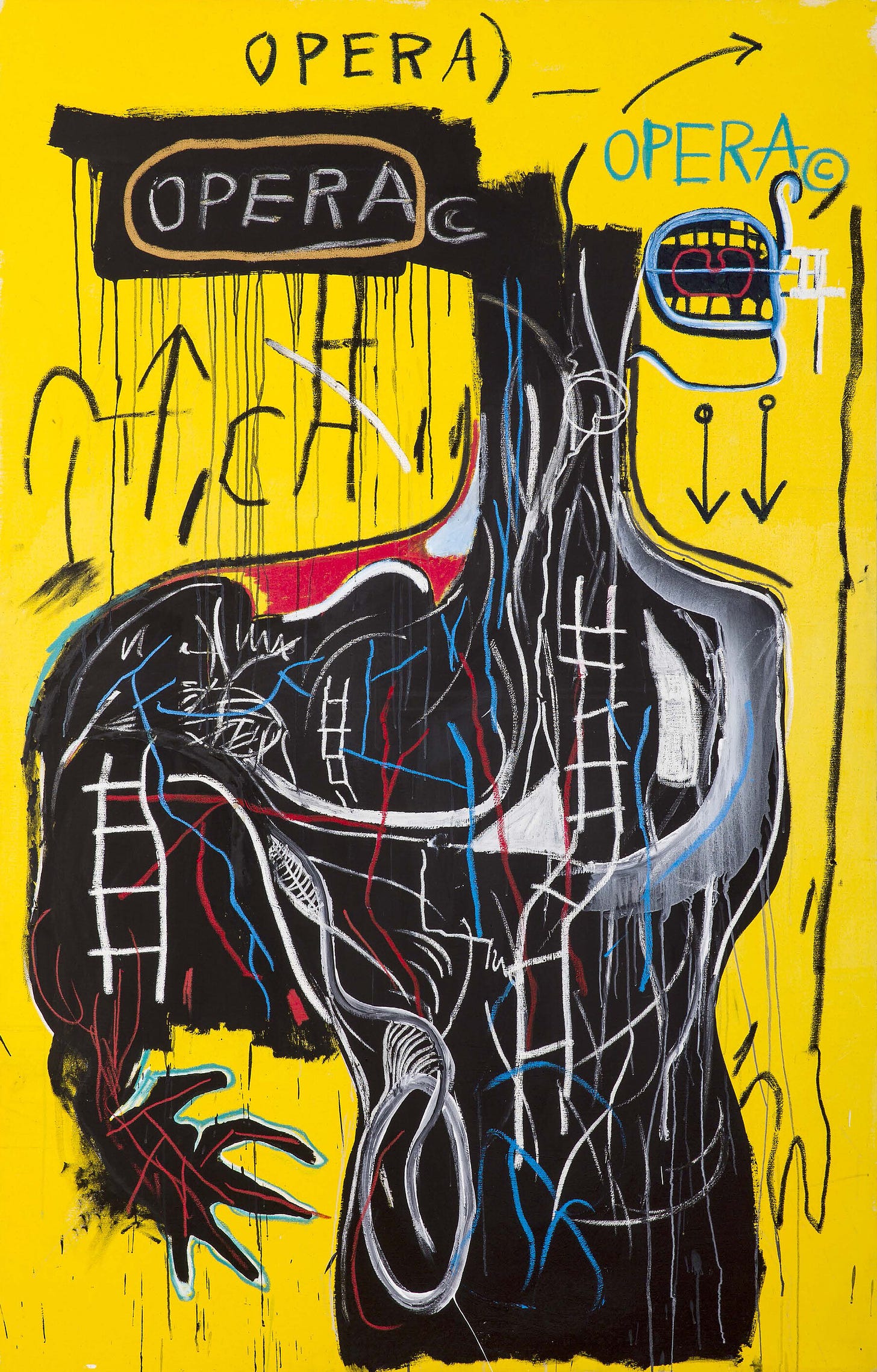

Anybody Speaking Words, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1982

Julle met Johan Schuster for the first time at the high school in Karlshamn. Schuster was the cool kid — straight edge, skinny jeans, the best drummer in town. (The town, on Sweden’s Baltic Sea coast, had 18,392 inhabitants.) When Schuster asked Julle what his favorite band was, Julle — who came from the farming country outside Karlshamn — said, “Michael Jackson”. Schuster laughed and shook his head. “Rage Against the Machine.”

Schuster could play any instrument he put his hands on; he’d had years of tutoring in a subsidized after-school music program. At the local branch of ABF, a Swedish worker’s organization started in 1912 to enable workers to self-educate, he borrowed a rehearsal space where he played math metal, death metal, and stoner rock. It all sounded magnificent to Julle.

For Julle’s birthday, Schuster wrote a song: Julle sixteen is a sex machine.

Julle had an idea. His sister, twelve years his senior, lived in Stockholm, and she was dating a music producer called Max Martin. This was in 2001, and Martin’s songs had just launched the careers of Backstreet Boys, ‘NSYNC, and Britney Spears (a trio of pop acts that were sometimes jokingly referred to as one band with rotating singers, since their major hits were all written and performed by the same Swedish musicians).

Maybe, Julle thought, his new friend could work with Max Martin?

Julle asked Schuster if he wanted to come along to Stockholm on the school break. They could watch Entombed, the Christian death metal band.

At the central station in Stockholm, Max Martin waited for them. In pictures, sitting next to Britney Spears or the Backstreet Boys, Martin had a long mane of glam rock hair; but he had recently let his girlfriend cut it, and now looked more like a guy who played Dungeons and Dragons. He wore thin-rimmed square glasses.

Julle, who had posted recordings of Schuster’s death metal songs to his sister hoping she would play them to Martin, tried to assess what impression his friend was making on the star producer.

“I think Martin liked him a lot right away”, Julle says in a 2015 interview with Swedish music journalist Jan Gradvall. “But I also think Martin felt that [Schuster] was incredibly annoying [. . .] with his arrogance and his preposterous style.”

On their next school break, going up to Stockholm again, Schuster confided in Max Martin that he too had started recording — in a basement that he shared with the local ping pong club. Martin listened. He said nothing.

A few weeks later, a man from a moving company knocked on Schuster’s door. He had several boxes to deliver.

It was a recording studio. Max Martin thought Schuster needed some encouragement.

Sweden’s scene creation engines

If you rank songwriters by the number of Billboard no 1 hits they have penned, Paul McCartney and John Lennon have been leagues ahead of the competition for more than fifty years. This is not true anymore. If Max Martin keeps up the streak he has had for the last 25 years, he will overtake Lennon this year and McCartney in a handful more.

And as incredible as this achievement is, Max Martin is just a part of a larger phenomenon: the so called Swedish music miracle.

In 2014 — the only year I have the exact numbers for — 25 percent of the songs that climbed to the top 10 in the US were written or co-written by Swedish songwriters. Over the past decade as whole, the number is somewhere between 10 and 20 percent. No country comes close to exporting as much music in relation to the size of its economy.

The main drivers of revenue are the big pop acts, ABBA and Roxette, and a stable of songwriters who write for The Weeknd, Taylor Swift, Coldplay, Nicky Minaj, Ed Sheeran, and a large share of other acts that have been on the top of the charts over the last three decades.

But the unusual success of Swedish music is not constrained to mainstream pop; it cuts across genres. Sweden has had an outsized influence on death metal (with bands such as In Flames, Meshuggah, and Opeth), house (Avicii, Swedish House Mafia, Alesso), indie music (Lykke Li, José Gonzales, Robyn), and so on and on.

Why is this happening in Sweden?

Several theories have been proposed, some less plausible than others. The dullness of long, dark winters is a common suggestion. The melodic nature of the language is another. It has also been pointed out that Sweden has the highest concentration of choirs in the world — eight percent of the population are active singers. Then there is the fact that Sweden, as a small economy, pushes musicians to write songs in English to find sustainable audiences.

Several of these theories likely contain parts of the puzzle. But the most important factor behind Sweden’s outsized success seems to be that Sweden by accident created unusually good conditions for musical scene creation.

What is a scene? It is a group of people who are producing work in public but aimed at each other. The metal bands in Karlshamn, where Schuster grew up, were a scene. They performed on stage — but the audience was mainly their friends who played in other bands. If they were anything like the other local scenes I’ve seen, they challenged and supported each other to be bolder, more ambitious, better. A scene, to borrow a phrase from Visakan Veerasamy, “is a group of people who unblock each other at an accelerating rate”.

Almost invariably, when you notice someone doing bold original work, there is a scene behind them. Renaissance Florence was a scene for scholars and painters, flowering in Leonardo DaVinci. The coffeehouses of Elizabethan London were a scene for playwrights, flowering in Shakespeare.

But scenes are hard to get off the ground. They need resources and infrastructure that enable collective and open-ended tinkering. This is rarely achieved at scale.

But it was exactly this kind of infrastructure that evolved in Sweden during the mid-twentieth century. It was not done intentionally. Rather, it was an accidental side-effect of two political projects that were subverted by the grassroots: the Swedish public music education program and the study circle movement.

Public music schools

In the 1940s, Swedish conservatives and church leaders were afraid that music imports from the US were leading to bad morals. They introduced an extensive and affordable after-school program for music. Kids could get tutoring 1-on-1 or in small groups for free once a week. They could borrow instruments, too. Later, fees were introduced, but around 30% of kids still receive free tutoring, and the fees only run up to about $100 per semester. About every third Swedish kid participates.

“Would you have been where you are today without the music school?” Max Martin is asked in the Swedish radio documentary Cheiron: a never-ending story.

“Absolutely not. And the rehearsal space — that was subsidized, too. You could borrow instruments and drums. I couldn’t afford that.”

The music schools introduced a large number of people to music making (“you learned to swim and you learned to play an instrument, this was just what was expected”). People did not, however, use the system as the conservatives intended. Instead, kids asked for lessons on how to play pop and rock.

The tutoring system also, unintendedly, became a subsidy for struggling musicians, who quit their day jobs to obsess over music while sustaining themselves by tutoring kids to do the same.

One of the tutors was a guy called Stikkan Andersson. While working at the music schools, he assembled a group of musicians named Anni-Frid, Björn, Benny, and Agnetha, and suggested they’d use their initials as a band name, ABBA. As they rose into the stratosphere, many Swedish musicians looked on and raised their aspirations.

But the thing that really accelerated scene creation came from another miscalculation.

Study circles

In 1902, Oscar Olsson, a secondary school teacher, was working in the temperance movement, which aimed to steer the culture away from alcohol consumption and toward service of the community. To further this aim, Olsson started what he called study circles. It was basically a book club. A group of people would meet and discuss a book, and through these meetings they would develop themselves, forge social bonds, and inspire each other to raise their aspirations.

The temperance movement successfully lobbied the Riksdag, Sweden’s parliament, to get funding to purchase books. This funding was channeled through various grassroots organizations to their members on the condition that the books were made available to the general public afterward.

This funding led to explosive growth in self-organized study groups. By the 1970s, ten percent of the population were active members. But the study circles rapidly drifted away from Olsson’s original intentions. Instead of being a tool to further the agenda of political movements, it became an almost permissionless infrastructure for learning. This was the result of a power struggle between the movements and the state: to receive state funding (which today makes up about 30 percent of the budget for study circles), the associations had to give up political control of the curriculum. But the state wasn’t able to wrestle control of the curriculum either — because of the strength of the movements. In a sort of exhausted truce, the control was ceded to the learners. Instead of ideological book clubs, people formed a myriad of learning communities: knitting clubs, discussion groups, and . . . bands.

(I have written more than you wanted to know about Sweden’s popular education movement before.)

The popular movements had built and repurposed numerous houses which are now open infrastructure for groups, like bands, that are involved in open-ended learning projects. It is hard to assess exactly how extensive this infrastructure is since it spans more than 20 popular movements, and many of the facilities are not registered, but we’re talking of somewhere north of five thousand learning centers.

Around many of these facilities, musical scenes have formed. Because of the ease of getting rehearsal space and small-scale funding, people are endlessly forming and reforming bands, as Johan Schuster was doing in Karlshamn. When I lived in Sweden, I would often spend my spare time in one of these spaces. There would be punk rockers sleeping on the floor — and then someone who had done the mixing on Britney Spears's debut album would pass through, or a dub artist from Ghana would start a jam, or you’d overhear stories from someone who’d toured with Bon Iver.

In Gothenburg, on Sweden’s eastern coast, an influential scene of indie bands formed (among them The Knife, José Gonzales, Jens Lekman, and Little Dragon) several of whom went to high school together. In the same city and era, what became known as the Gothenburg sound, or melodic death metal, was invented. In Stockholm, apart from the mainstream pop and house music acts, there have been scenes in numerous genres — hiphop, punk, electro, even a sizable K-pop scene of writer-producers that supply South Korean stars with tracks.

The infrastructure provided by the music schools and the learning centers created fertile breeding grounds for scenes. This is where Max Martin, Johan Schuster, and nearly every other musician mentioned in this piece, spent their formative years.

And out of this breeding ground, another institution grew: the tradition for established songwriters to find young talent and nurture it through apprenticeships.

The disciples of PoP

The founder of the lineage of producers that Max Martin belongs to was a DJ named Dag Volle.

Over just six years, Volle, who used the stage name Denniz PoP, trained (at least) nine songwriters who went on to define the sound of modern pop by supplying the hits for first Backstreet Boys, Celine Dion, and Britney Spears, and then Kelly Clarkson, Pink, and Maroon 5, and then The Weeknd, Ariana Grande and Adele — several hundred hits in total.

The first time Max Martin met him, PoP had just risen to producer stardom after launching the Swedish band Ace of Base to the top of the US charts, helping them sell 50 million albums over time. Martin, who was the singer in It’s Alive, a glam rock band that PoP had signed, was anxious to make a good impression. But when they sat down to work on the songs, Martin noticed how Pop fumbled among his papers for instructions showing him where to put his fingers on the keyboard.

Denniz PoP was not a musician. What he had instead was taste — a tacky taste, perhaps, but also one the was profound. In an interview recorded for Swedish Public Radio sometime in the mid-90s, PoP recalled:

“I bought a cursed amount of singles. I didn’t play any instruments. My only interest was buying singles and owning them and listening . . . I was a single’s man.”

The decade before he rose to stardom, Denniz PoP had spent playing records in pizzerias and bars and (increasingly hip) clubs. Unlike other DJs, he was entirely uninterested in trends (something he signaled by taking the tackiest name he could think of). The only thing he cared about was what he liked and what made people dance. He would study the dancefloor as he put on single after single; he noticed what made them go wild and what made people remember that they needed to go to the toilet. To make the songs more effective, he made mixtapes where he cut out the boring parts and improved the beats.

The deep tacit knowledge he developed through this practice — his taste — allowed him to notice when someone had an ear for melodies like Max Martin had. PoP was always on the lookout for that — asking friends for introductions, keeping the door of his studio open so that local musicians could walk in off the street and play him songs. He needed every good songwriter he could find.

And his capacity to spot talent early was unnerving. When a songwriter PoP was training returned from a workshop at a local middle school, PoP was told a girl had sung a moving song about her parent’s divorce. PoP invited her to the studio. Her name was Robyn. A few years later — when she was sixteen — she too climbed into the Billboard top ten.

PoP liked to connect unconnected parts of the social graph and watch how ideas that had arisen in one part spread to the rest. The songwriters he brought together came from an eclectic mix of scenes — and he hooked them up to the US music industry. When he set out to do this, the US music industry was almost entirely decoupled from the non-anglophone world. No songwriter from outside the US and the UK had been able to establish themselves as songwriters for US pop stars. But following the success of Ace of Base, PoP had set out to do just that.

At first, he had no success securing collaborations with the labels in Los Angeles. But then he landed a contract with Zomba, a conglomerate of labels headquartered in Orlando, Florida. Zomba had put together a new boy band called Backstreet Boys, which Denniz PoP was to supply the songs for. This was the deal that allowed Denniz PoP to bridge the gap between the US music industry and Sweden’s music scenes. Musical innovations that had evolved in the periphery flowed to the center.

How to teach taste

Max Martin and the other adepts of PoP had all been schooled by music tutors and shaped in various scenes. But it was at PoP’s studio, named Cheiron after the centaur that taught Dionysus to sing and dance — it was here that they learned how to turn music into hits.

“I didn’t even know what a producer did [when I came to Cheiron],” Max Martin recalls in the only English-language interview he’s done to date, for Time Magazine in 2001. “I spent two years — day and night — in that studio trying to learn what the hell was going on.”

Like his PoP, his adepts more or less lived in the studio — PoP’s son, too, grew up there — and PoP would put his fingers into every song that was written. In a Swedish TV documentary called “The Nineties,” Swedish singer E-Type describes the working conditions at the studio:

“I get this feeling of a big painter’s studio in Italy, back in the fourteen-hundreds or fifteen-hundreds. One assistant does the hands, another does the feet, and another does something else, and then Michelangelo walks in and says, ‘That’s really great — just turn it slightly. Now it’s good. Put it in a golden frame, and out with it. Next!’”

The standards were high, the tempo slow — mixing a song often took several weeks.

But the atmosphere was also open and playful. PoP’s adepts could walk in whenever they wanted and sit down next to him while he joked with the nervous kids in the Backstreet Boys, or played video games with his son, or meticulously crafted songs and sounds1.

PoP also passed on the method he had used to develop taste. Max Martin and the other adepts were sent around the clubs in Stockholm carrying up to a hundred different versions of each new track, so they could study which combinations of beats and melodies made the clubs go wild.

Apart from these adventures to the club, though, they paid almost no attention to the outside world. Rami Yacoub, who was trained by PoP and has written the Nicky Minaj song Starships among several other hits, says in “The Cheiron Saga”, another radio documentary:

“We didn’t care about what was happening in the rest of the world. We ate at odd hours. We worked at odd hours. We slept together in weird places. It was its own universe. And what did this give us? It gave us a healthy respect for what is possible. We did things that we liked, and that we thought were funny and weird.”

Notice that this is how someone in a scene talks. It is all about trying to impress and entertain your friends, pushing each other to refine your taste and your skills. This is how you push the edges of your craft.

By 1997, the studio team that PoP had assembled were the most influential producers in the world, following the success of Backstreet Boys. American labels flooded to Stockholm.

But something was not right with PoP. He found it increasingly hard to eat. He experienced fatigue.

In November 1997, he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. He was 34 years old.

When he grew too sick to work, the studio was put in the hands of Max Martin, who had by then worked there as an assistant for three years. Martin would visit PoP at the hospital to play him voice memos of songs he was working on, to get PoP’s feedback. One of the last songs Martin played PoP, a demo he had recorded while falling asleep in bed, ended with a part where Martin mumble-sang “hit me baby one more time . . . yeah, that’s pretty good”. PoP told him to go ahead with that one.

In August 1998, he passed away.

The Third Generation

When Johan Schuster, the drummer in Karlshamn, was given a recording studio by Max Martin, Pop had been dead for three years. Max Martin, feeling that the work had become mechanical and predictable after PoP passed away, had closed down the Cheiron studio.

He had set up a new studio, Maratone, but the years of success were over. No one wanted to sound like a boyband in 2001. Martin and his collaborator Rami Yacoub sat in a beautiful, well-equipped studio, alone, writing b-sides. The buzz and madness of Cherion, where the studios were filled with multiple teams writing songs and kids playing and artists walking in off the street — it was gone.

On school breaks, when Schuster came to Stockholm with Martin’s brother-in-law Julle, Martin would try his best to get Schuster to write a pop song. Schuster thought it was ridiculous — three chords and en rövtext, shit lyrics — but he did a few attempts. Maybe, Martin said, you shouldn’t have a one minute guitar intro.

When Julle turned twenty-one, Schuster, as was his tradition, wrote a birthday song: “Julle, you’re a flower”. Julle, as was his tradition, played it to Martin.

Martin called Schuster. That was a real pop song, he said. How would you like to come up to Stockholm for an internship?

When Schuster came to the studio, Martin pointed to a chair in the corner of the control room. In “Cheiron: a neverending story”, Schuster recalls Martin saying:

“Just sit in that chair and be silent. You will make coffee, get us food, and just sit there. Watch and learn.”

How do you write a hit? There is no recipe — the landscape is always changing, as sounds grow worn and trends move on. To be successful in such a landscape, you need taste. PoP had developed taste by obsessing over singles with other DJs, noticing how the music made him feel and why, studying how it made people behave on the dancefloor. He passed this taste on to his disciples, by forming a community of practice, a loose apprenticeship where peers and masters could learn from each other. This way of cultivating talent had come naturally to PoP. He was an inherently generous and playful guy, who had a great capacity to make people feel included and seen. But Max Martin was not like this. He had to learn it.

After three years of failed attempts at writing hits on his own, Martin had realized that he needed to recreate the atmosphere at Cheiron. He decided to bring in new talent, help them grow, and channel the sensibilities they had formed in various scenes into new hit songs. Around the time Schuster joined the studio, Martin, with the help of this new generation of writers, was indeed again making hits.

Schuster would sit on his chair and watch them work. At night, when Martin left the studio, Schuster was given the keys and was told to write songs. In the mornings, Martin asked Schuster to play him the new stuff. He would give feedback and, if he saw some potential, he would ask Schuster to stay on in the evening again and record a demo.

So to return to the question: How did Sweden become such heavyweights in the music industry?

By giving people like Schuster the chance to obsess over music. By giving them cheap tutors and free instruments. By providing infrastructure for scenes, where they could egg each other on. And through the apprenticeships which formed around people like Denniz PoP and a number of his adepts.

(I’ve written before about the childhoods of exceptional people, and Schuster’s learning pattern in key ways matches that of people like Blaise Pascal, J.S. Mill, and Virginia Woolf: he grew up immersed in a milieu, a scene of muscians; he was tutored one-on-one; then he got apprenticed to a master in his field.)

When Schuster had been in Martin’s studio for about a year (of his intended two-week internship), the American pop star Pink came by. Martin told her he had a new song for her and put on one of the demos that Schuster had recorded, a “silly Deep Purple riff”. In the chorus, the boy from Karlshamn belted:

So, so what?

I'm still a rock star

I got my rock moves

And I don't need you

Pink told Martin she’d love to work on that, and Martin waved the stunned Schuster over from his chair and told him to help Pink finish up the track.

That song, So what, became Schuster’s first release and his first no 1 on Billboard.

He has now, under the pen name Shellback, written ten more that have peaked at no 1, making him one of two Max Martin disciples among the ten most prolific writers of chart-toppers in history (the other one is the American songwriter Dr. Luke).

However, having written a hit song did not make the 21-year-old Schuster a mature songwriter in the eyes of Max Martin. After the success, he had to go back to making coffee for the team.

“I was the coffee boy for three or four years. I had three no 1s in the US before I stopped making coffee. For real. But that was a part of the education, too: to be held hard and kept on the ground.”

Warmly

Henrik

If you’ve made it all the way down here and don’t feel like you’ve just wasted fifteen minutes, consider giving the essay a like. It helps others find it. And it makes me happy! If you have friend who would enjoy my essays, it is really lovely when you share it with them, too.

PoP’s approach is similar to what MrBeast, in the last post I wrote, calls cloning: “the guy who’s basically my right-hand man right now, two years he lived with me. And we probably talked on average those two years, seven hours a day. Anytime I had a phone call, I’d throw it on speaker and I’d let him listen. Anything I was reading, any content I was consuming — like really training his brain to think like me.”

Dear Henrik, this is such a fantastic essay. The way two separate learning processes have contributed to a behemoth of musical excellence and expression is a wonderful story or movie waiting for you to pen down. This reminds me of an experiment done in India, probably sometime around 2005 (?) , a group set up PCs in a box without any instructions in an economically disadvantaged section. Within a week, kids had self taught themselves on how to use it and were passing the learning.

Opportunity is a huge blessing, as it seeds possibilities.

Thank you again for a superb piece

Shirish

This is a fun documentary. There's no Part 1, but there's parts 2-6 about the Swedish pop miracle, where you get to see many of the guys you write about in action.

https://www.youtube.com/@leighhutton3549/videos