There are certain works—paintings, films, books, gardens—that have an effect on me that I can most simply describe by saying: in their presence, I remember that I am a human being. In this series, I write about these works.

See also, part 1 about Herzog’s Into the Abyss, part 2 about Shostakovitch “String Quartet no 8”, and part 3 about Tomas Tranströmers Baltics.

Repeat great words, repeat them stubbornly

“Freedom is a heavy load, a great and strange burden for the spirit to undertake. It is not easy. It is not a gift given, but a choice made, and the choice may be a hard one.”

—Ursula K. LeGuin, The Tombs of Atuan

Part 1: Los Angeles, 1970

I.

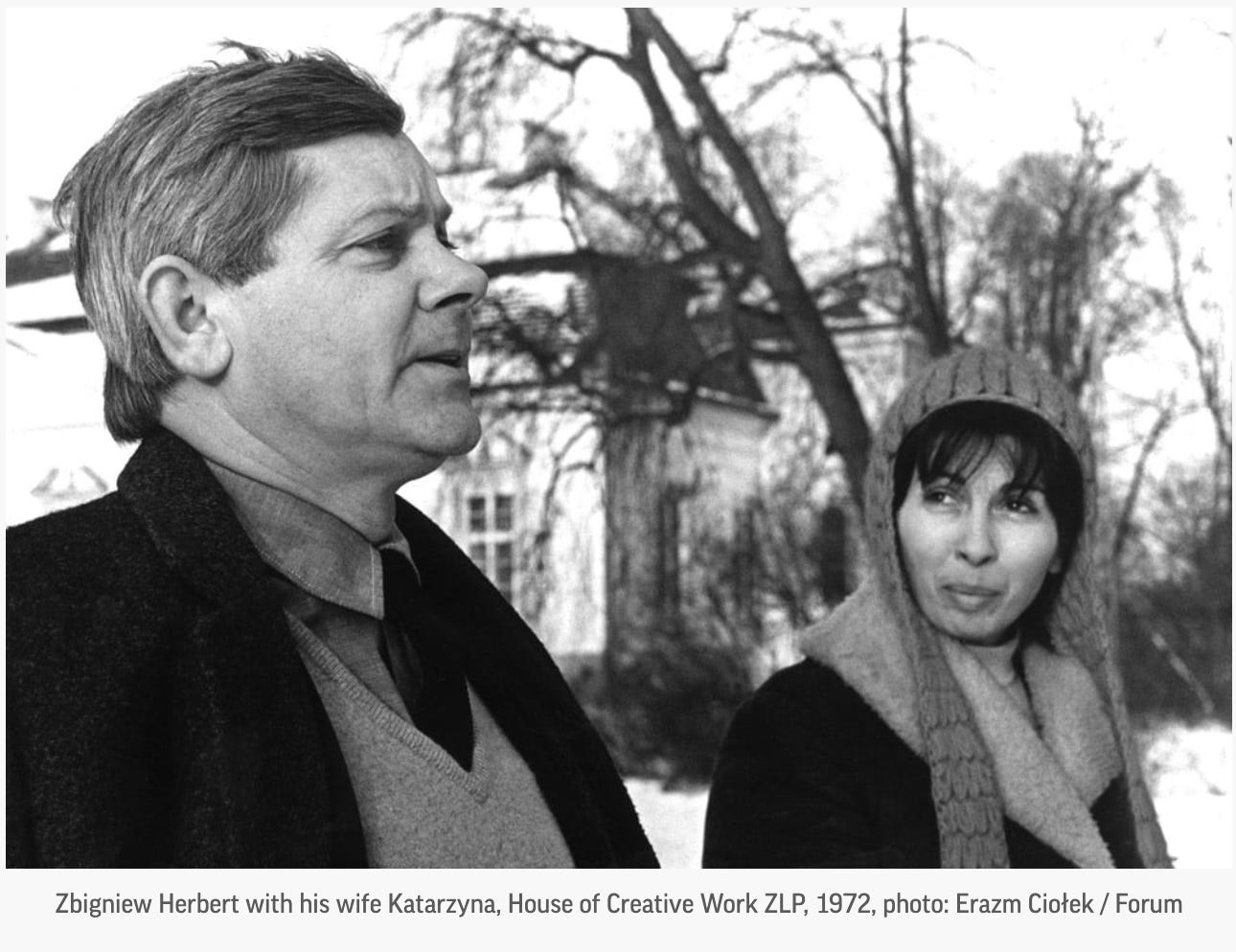

The Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert was teaching European literature in Los Angeles when the news reached him about the protesting shipyard workers in Gdańsk. On the evening of the 16th, 1970, the Polish vice prime minister Kociołek had called for the workers to break the protest and return to work. Those who complied and took the morning train to work were met, on the platform, by the police and the army who opened fire into the crowd. Here and elsewhere, 44 civilians were killed and more than a thousand wounded.

In “Strange Days”, an essay set against the backdrop of these months of protest and massacre, the American poet Larry Lewis, who acted as Herbert’s driver in Los Angeles, captures the alienation Herbert experienced in California. Herbert was spending his afternoons being driven through suburbs, painted in pale shades of yellow and green and pink, while the dead were carried through the streets of Poland. He listened to his students talk about peace and how it would come if we could just love each other more. In the L.A. Free Press, while the Soviets ousted the leader of Poland, Herbert read about the revolution.

“What does this word mean here, revolution?” Herbert asked Lewis. “They use it on every page. Here,” Herbert handed him the paper.

“Oh, scented oils,” Lewis said. Revolutionary scented oils.

It was here, in this liminal California—floating past Taco Bell and Carpet World and Shell Stations in the back of a car, while his country sank under the weight of the Soviet Union—that one of the most memorable characters of 20th-century poetry took shape in the mind of Zbigniew Herbert.

II.

Mr Cogito will be numbered

among the species minores

With his petty fears, his passing interest in pop art, and his ability to read the news without taking in the scale of the horrors that pass before his eyes, the pathetic Mr. Cogito, nevertheless, struggles earnestly to live ethically—

Mr Cogito

would like to stand up

to the situation[...]

however he doesn’t have

a sword

nor the opportunity

to send his family overseastherefore he waits like the others

walks back and forth in a sleepless room

despite the advice of the Stoics

he would like to have a body of diamond

and wings

The Mr Cogito poems, which Herbert began in Los Angeles and continued to write for the rest of his career, are ethical meditations in the form of ironic free verse. Unlike most moral poetry, you don’t feel talked down to by Mr Cogito. It isn’t a sermon. Instead, it feels as if you’re overhearing Herbert talk to himself. You’re listening to Herbert, who would prove himself to be one of the more upright persons of the last century, tell himself what he needs to hear to be that sort of person.

III.

“The Envoy of Mr Cogito”—the first and most famous of the Cogito poems—opens with the lines,

Go where those others went to the dark boundary

for the golden fleece of nothingness your last prize

That is, the poem is reminding the listener (who I take to be Mr Cogito, or Herbert himself) that he already knows what he should do. He knows where he would go if he had moral courage. He would go back to Poland. Even if it means crossing the “dark boundary” into “nothingness.”

you were saved not in order to live

you have little time you must give testimony

But he knew that if he returned he would have to live in a wire-tapped apartment; his conversations would be recorded and used against him. He knew he would lose the luxuries he had in Los Angeles—the late nights in Polanski’s Hollywood Hills mansion, the long drives with his wife to the Grand Canyon. As someone unwilling to compromise, he wouldn’t just reach normal communist poverty; he would be blocked from all decent-paying work.

What Mr Cogito was asking of himself (and of Herbert) was, it can seem, too much. Yet, at the same time, these ethical standards did not feel like demands. It was not a question of what he should do; he wasn’t compelled to return to Poland by an external moral code. It was what he felt was right.

Coming from a self-ironic and humble character, the ethical demands of the Mr Cogito poems remind me of an insight I got from reading Joe Carlsmith: one way to think about the root of ethics is in terms of faithfulness to what your heart tells you. Ethics is about seeing yourself more whole so you do not betray what you love through confusion or cowardice. It is not an external authority that demands things of you. It is not a list of commandments you have to follow. Ethics is care. This is how I read Mr Cogito.

IV.

One day, on a ride through the suburbs east of downtown L.A., Lewis asked why Herbert didn’t have his own car.

“You never drove, Zbigniew?”

“Once. I drove once, yes.”

“When?”

“It was after a meeting of the Underground,” he said. “The boy who drove for me was waiting in the car. But dead. The Nazis shot him. Just one shot, a style they had. I came out later . . . I saw him. I had to learn fast. I pushed the boy over to other side of car seat. I drove. Just one time. With the dead boy beside me. I drove.”

Mr. Cogito

has made up his mind to return

to the stony bosom

of his homelandthe decision is dramatic

he will regret it bitterly

Part 2: Warsaw, 1971

I.

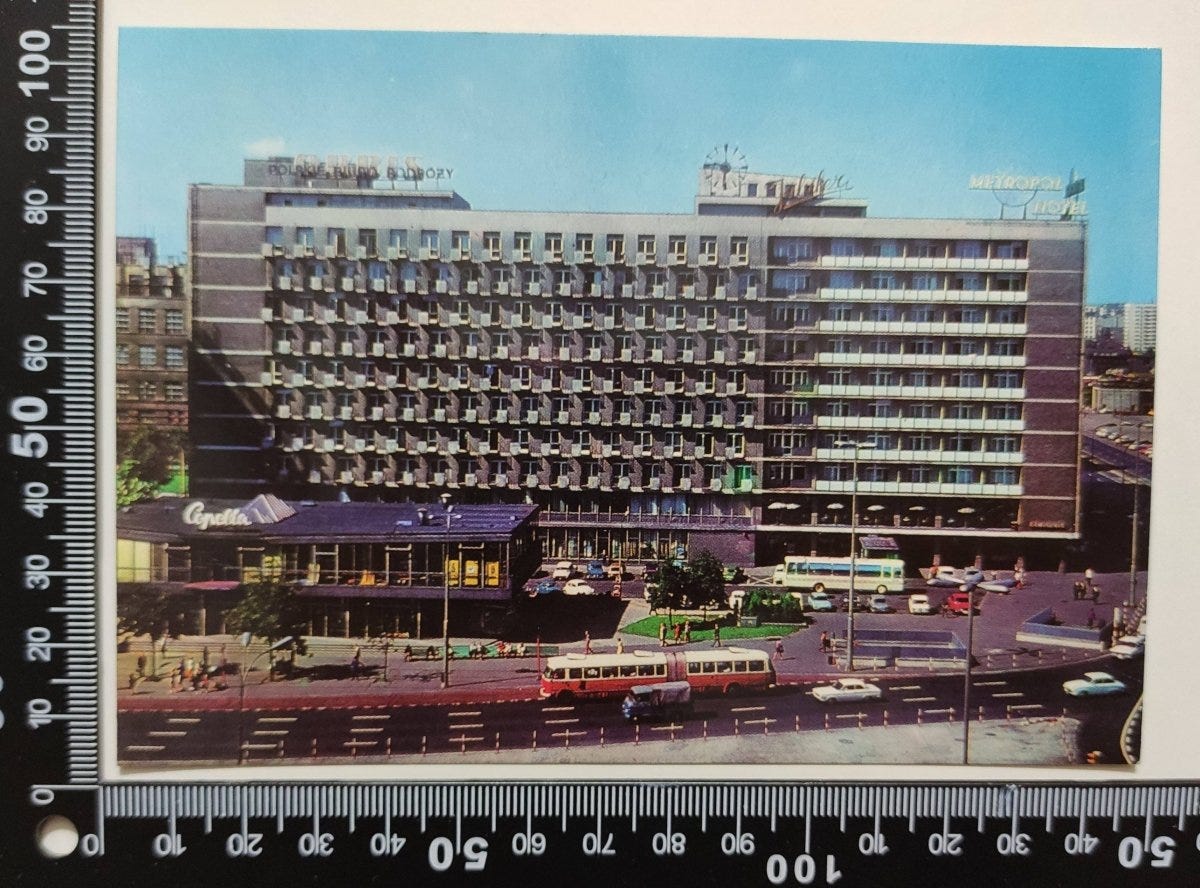

This was the Metropol Hotel in Warsaw:

In a letter to Czeslaw Milosz, a Polish poet who stayed in California and would go on to win the Nobel Prize in 1980, Herbert described the experience of being invited to the Metropol Hotel after returning to Poland:

I hadn’t expected to feel the touch of the gentlemen in little black suits. They phoned me on the day after I arrived. [...] Then there were regular daily “conversations” lasting many hours, not at headquarters—God forbid—but at the top of the Metropol Hotel, with a window open on the courtyard. I could [fall out of the window] and my friends would say I’d been drunk[.] They were interested in many things, among them Trotskyite movements in the West, but mainly the émigrés, whom they would most like to lure into their pit. They asked me all about you, too, whether you might not come back, and I summarized The Issa Valley for them and analyzed your poetry, pretending you interested them as the best living Polish poet. I played the fool, but it was no fun. I was alarmed to find that I wasn’t used to it anymore, that I wasn’t good at strolling around with shit on my head, and that I’m a coward because I fear for the rest of my life.

As Herbert told himself in “The Envoy of Mr Cogito”, you had to accept that—

the informers executioners cowards—they will win

they will go to your funeral and with relief will throw a lump of earth

—and still “love the morning spring / the bird with an unknown name the winter oak”.

You have to see the world for what it is, in all its brutality, and you need to do this while keeping your heart soft for the beauty that makes it all worthwhile.

II.

Of the last 176 years, Poland had spent 155 occupied or controlled by, first, Prussia, Russia, and Austria, and then—after a brief period of independence—Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

Because Polish literature came of age under occupying regimes, it is perhaps unsurprising that Polish authors have developed a rich tradition of parables. Unable to talk about the Kulturkampf where the Germans tried to eradicate Polish culture, Sienkiewicz wrote about Nero’s persecution of the Christians. Unable to talk about the slow collapse of the Polish state, Kapuściński traveled to Ethiopia and interviewed former courtiers at Haille Sellasse’s court about their downfall.

By cutting away the details of the political cage fights of the day, parables lay bare the repeating deep nature of human drama.

It can be strangely relieving to realize that what you are seeing around you is nothing new, and that the horrors that humans inflict on each other follow a pattern. But the good thing is that it is not only the darkness that repeats—the proper response, too, has been similar in era after era.

We might confuse ourselves in the present moment (because of our biases and fears) but what is right and what is wrong is harder to miss when we see the patterns of our times repeated in histories from the Inquisition, a Coup d’Etat in Central Africa, or in a parable about animals who make a revolution on a farm. There is something grounding in this. We know what to do.

There is a sense in which Herbert, by writing in allegories, by mirroring his times in the past, is taking the side not of Poland (nor a particular party in Poland), but of the underlying project we call civilization. I mean the ever-unfolding attempt to create a habitable world, a world of positive-sum games, virtues, individual dignity, and stable institutions. Every single decision made by every single human being who ever lived, either made a small push toward this or a small push away. And it is this underlying struggle that Mr Cogito is engaged in.

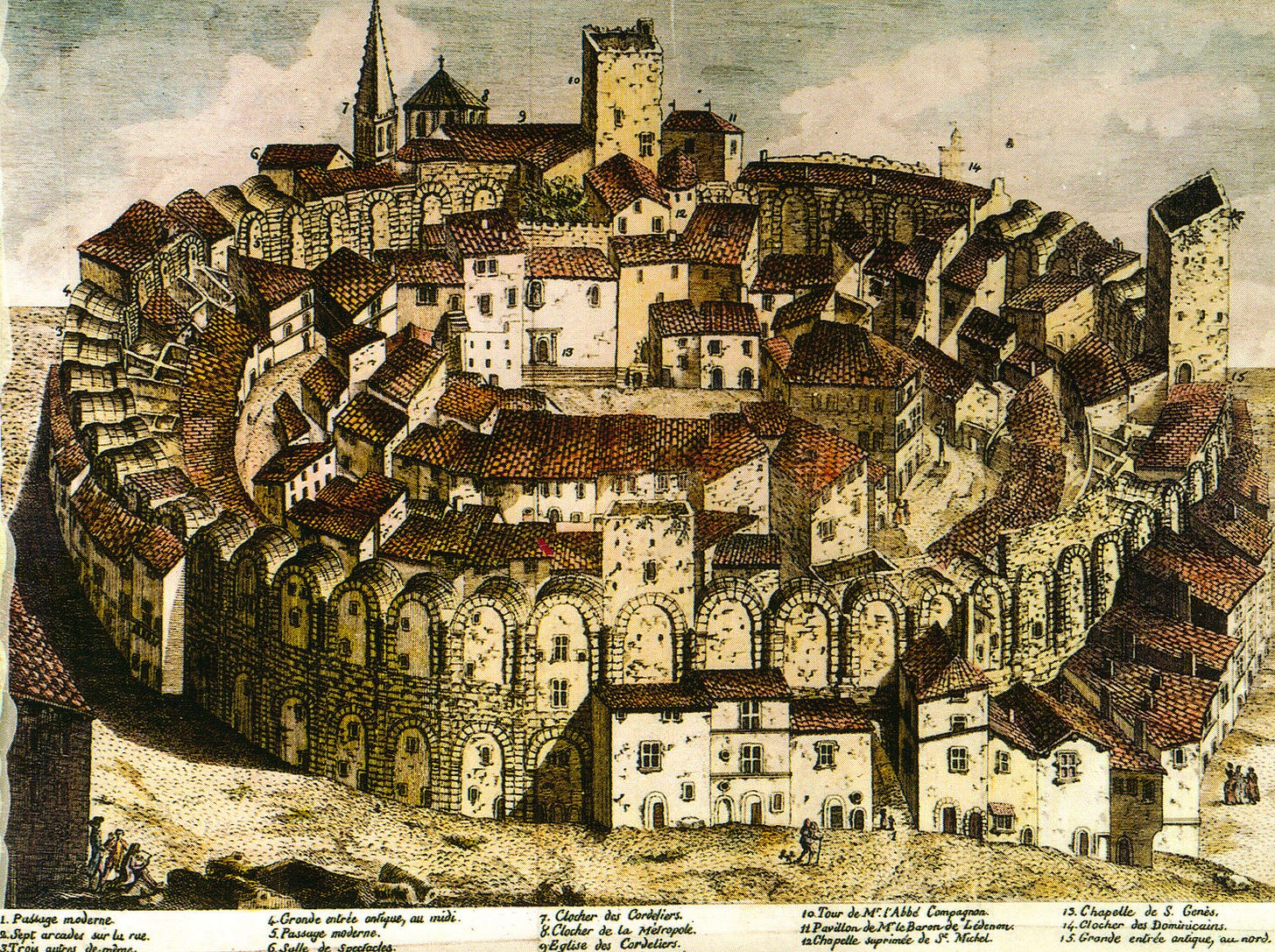

In Barbarian in the Garden, Zbigniew Herbert relates an anecdote about the amphitheater in Arles, France, which can serve as a meta-parable for what Herbert was doing:

The amphitheatre’s walls were so thick that during the barbarian raids the construction was turned into a fortress. Inside, streets were laid, with a church and some two hundred houses. This strange hybrid remained till the seventeenth century.

As the barbarians, in the form of party officials who cared not about human dignity but power, undermined the institutions and norms that made life bearable, Herbert sought refuge in poems, statues, songs—the remnants of civilization. The barbarians could wiretap him, they could harass him by leaking reports about his stays at West German psychiatric hospitals, they could—as Herbert had seen the Nazis do to one of his friends during the war—rile up pigs until the pigs tore a human body apart. But they could not, by force, take civilization out of him. Civilization had a town in the amphitheater of his mind.

repeat old incantations of humanity fables and legends

because this is how you will attain the good you will not attain

repeat great words repeat them stubbornly

III.

In 1974, three years after his return, Herbert will publish “The Envoy of Mr Cogito”. The magazine that runs the poem will sell out in two hours, turning Herbert into a symbol of ethical courage.

In 1980, when the State declares martial law, he will throw his full weight behind the opposition. As a fissure of resistance opens up, his poems will be recited and sung at rallies—they will be sung over and over again as the fissure spreads and branches across the Eastern Bloc until it cracks the entire Soviet Union.

But all of this is, when he returns to Poland, still an unknown future. He does not have the luxury of knowing the story will end—against all odds—happily. All he has, as he writes his poems, is uncertainty, fear, his wife, two cats, and a sofa to sleep on in Artur Międzyrzecki’s apartment.

keep looking at your clown’s face in the mirror

repeat: I was called—weren’t there better ones than I

It is in this uncertainty, he must decide how to act.

For a sample of Herbert’s poems, see here and here.

Like all essays on Escaping Flatland, this one was funded by the generosity of subscribers. Thank you! If you find reading the essays meaningful, consider supporting.

Thank you Esha, Jack, and J for input on the draft.

Thank you for the introduction to this poet. You have inspired me to reserve a copy of a recently published collection of his work at my local library.

I really enjoyed reading this. Thank you.