In 2015, I amused myself by training a neural network to generate poems in the style of various poets I knew and submitted the results to a fanzine. The thing I built was a primitive language model and—though I thought it was fascinating, seeing a computer talk—it did not occur to me that it could be useful for much beyond pranks. I would never have guessed that seven years later, the same basic idea scaled up would be intelligent enough to pass university exams.

When projecting where technology is going, it is tempting to assume that the future will be like what we have now—just a little more of it. This is often true, but sometimes, as the physicist Philip Anderson said, more is different.

Together with artificial intelligence, let’s consider two other trends that are taking off right now: solar power and batteries. Like AI is driving down the cost of (more and more kinds of) intelligence, solar and batteries are driving down the cost of energy. How will more be different here? Intelligence and energy are core inputs in the economy: increasing their supply will likely impact nearly every aspect of society. Where are we going?

A note on intent: I’m writing this to prepare myself for a larger project that explores the future of education. Education does not feature in this post, but it determines the scope. I’m not attempting to predict the future (that sounds overwhelming!) but simply collect some notes on trends in AI and the energy sector, trends that will have an effect on education (and nearly everything else).

AI in the near future

If it is weak thinking to assume things will stay roughly the same, a slightly more rigorous approach is to look at historical rates of development and model what would happen if the development continues at that rate.

The research group Epoch has collected this type of data, showing that the trend for AI is:

a doubling of hardware efficiency every two years;

a doubling of algorithmic efficiency every year;

and a doubling of economic investments in AI every six months as of late.

When you multiply this together the growth of effective compute for AI is dramatic, and will likely be so for at least a few years more. (If this trend were to continue for another ten years, all GPUs and skilled software engineers and physicists in the world would have been diverted into AI development—all resources would be gobbled up—so either we hit a full-blown intelligence explosion within a decade, or the trends will slow as they reach a natural constraint.)

Seven years ago, you could use AI to make nonsense poems with garbled grammar. If we project seven years into the future, what can we expect the growth in effective compute to enable by 2030?

In what follows, I will rely on projections by Jacob Steinhardt at UC Berkeley and Carl Schulman at the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford. I’m not an expert in the field, and I can’t evaluate how accurate Steinhardt and Schulman are, but they strike me as more systematic in their approach than most others who discuss AI.

Two sectors that will be affected early by the coming capabilities are mathematics and AI research itself. These fields are well-suited to the strengths of AI systems and are also economically immensely valuable, so they will be natural places to focus on for AI companies.

Steinhardt predicts that AI models by 2030 will be “better than most professional mathematicians at proving well-posed theorems.” And given that there are “not that many mathematicians in total in the world,” AI systems in 2030, “could simulate 10x or more the annual output of mathematicians every few days.”

Developing AI systems is increasingly labor intensive—every year, you need more and more people to make the same amount of progress as you did last year. But if part of the “labor force” that is AI itself is diverted into AI development, it might be more than enough to compensate for the increasing labor demands. At current growth rates, AI companies in 2030 will have enough compute to perform ~1.8 million years of work when adjusted to human working speeds.

Carl Shulman:

The way to think about it is — we have a process now where humans are developing new computer chips, new software, running larger training runs, and it takes a lot of work to keep Moore's law chugging (while it was, it's slowing down now). [...] But how much harder? [...] In this paper they cover a period where the productivity of computing went up a million-fold, so you could get a million times the computing operations per second per dollar. A big change but it got harder. The amount of investment and the labor force required to make those continuing advancements went up and up and up. It went up 18-fold over that period. Some take this to say — “Oh, diminishing returns. Things are just getting harder and harder and so that will be the end of progress eventually.” However in a world where AI is doing the work, that doubling of computing performance, translates pretty directly to a doubling or better of the effective labor supply. [...] We're getting more than one doubling of the effective labor supply for each doubling of the labor requirement. In that data set, it's over four.

If we reach the point where AI systems are used to enable faster progress on the AI systems themselves—something that might already be happening at a small scale—a feedback loop opens up. The outputs of the systems (mathematical theorems, code, decisions) become inputs driving further development.

The systems of 2030 will likely also be able to share knowledge between copies of itself running in parallel. A descendant of ChatGPT could be deployed to millions of users, learn something from each interaction, and then propagate gradient updates to a central server where they are averaged together and applied to all copies of the model. In this way, the system can observe more about human nature in an hour than humans do in a lifetime, which allows it to rapidly learn any skills missing from the training data.

Falling energy prices and economic growth

Two other important trend that are taking off at the moment are the build out of solar power and battery farms. Until recently, I was skeptical we would be able to turn our energy systems around in time to stop catastrophic climate change; it now seems I was wrong about this (though it is still a gargantuan task).

In advanced markets, it is already cheaper to build and operate a solar farm than to continue operating a legacy thermal power plant—the operating costs of even a brand-new coal or gas power plant are higher than the construction and operating costs of a new solar plant.

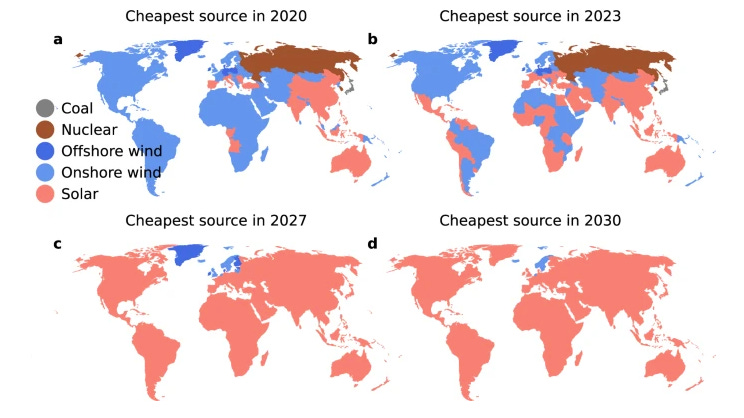

This diagram from a recent article in Nature shows the cheapest source of energy in different countries if the price drop on solar power continues. My native Sweden will be one of the few places where solar will not be the cheapest option by 2030; there it will be wind power.

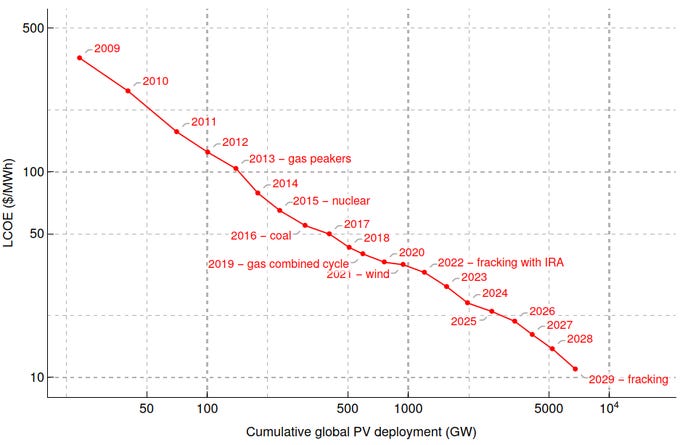

By 2029, solar power will have outcompeted fracking as the most cost-efficient way to produce energy overall, as shown by this graph which plots the cost of solar power over time:

In 2022, it was projected that 1 TW of solar will be deployed annually by 2030—which I take to be comparable to roughly 200 nuclear power plants per year. It now looks like we will reach that by the end of 2024. We’ve never seen a transformation of the energy market this rapid. By 2050, the authors of the article from Nature projects, solar will have become the dominant energy form globally (though there is a question if government agencies in developed countries will be able to approve renewable power plants at a fast enough tempo).

Furthermore, solar power has a synergetic effect with battery farms. Battery farms make solar more valuable by providing storage for when the sun goes down. And battery prices are plummeting much faster than expected too:

Prices have come down a long way since January 2010, when Boston Consulting Group estimated battery costs at between $1,000 and $1,200 per kilowatt-hour. It said getting to $250—a level car makers were targeting—“is unlikely to be achieved unless there is a major breakthrough in battery chemistry.”

Today, battery prices are about $125 per kilowatt-hour.

This is from an article in the Wall Street Journal three years ago.

It is now possible—and a great investment—to build large battery farms that buy electricity when it is cheap and sell it when the prices go up. This undermines the profit marginals of coal and natural gas plants that have to shovel their profit over to battery owners while making solar more valuable. The number of battery farms in California has grown by 10X since 2020. They pay for themselves in two years currently.

Because of the incentives of a battery-centered energy market and the rapidly falling costs, Casey Handmer argues renewables will be scaled out far beyond our current needs—building 5-15x overcapacity. At that level of overcapacity, electricity is basically free, compared to today’s standard, and we can expect continually dropping prices for at least a few decades more.

Apart from being an important step toward addressing climate change, solar power and falling energy prices will likely also shift the rate of economic growth. The last time we saw consistently falling energy prices was before 1971, which was also the last time the West had rapid economic growth. There are many things that solve themselves if energy gets cheaper all the time, and the end of this trend has been conjectured as one cause of the relative stagnation of the last half-century. When energy price drops resumes after a fifty- or sixty-year pause, a reasonable second-order effect is that economic growth goes back up to levels not seen in my life time. (AI will push the economy in this direction, too.)

There are many interesting things we can do if energy isn’t a bottleneck. It will become economically feasible to water the deserts and suck carbon dioxide from the skies, turning it into renewable jet fuel, and so on.

But the big question is: what happens when falling energy prices intersect with the falling price of intelligence? As Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, put it in an interview recently:

Someone will still be willing to spend a significant amount of money on computing and energy, but they'll get an unimaginable amount of intelligence and energy in return. Who will do that, and where is it going to get weirdest? Imagine energy becoming 100 times cheaper [which would require fusion reactors at scale, not just solar], intelligence 100 million times cheaper, yet people are willing to spend a thousand times more in today's dollars. What happens then?

Do sensible human things

I notice an apprehension in me as I make these notes. When you plot the trends out, it is hard to rule out that the future could turn into a Hieronymus Bosch painting, a weird, distorted landscape filled to the brim with suffering, excess, and madness.

There will be magnificent possibilities—AI tutors for everyone; individual empowerment; accelerated scientific, technological, and medical progress; reversal of climate change; deserts blooming—but there will also be political turmoil; mass labor displacement; geopolitical shifts; increased surveillance and targeted manipulation; leverage to violent individuals and organizations; autonomous weapon systems; and AIs that could end up power grabbing and pursuing objectives that threaten human existence.

This essay isn’t the place to weigh the relative probabilities of these outcomes (which I’m not even sure is a meaningful thing to do). But I want to note two things. First, human beings have agency, we’re not destined to hurtle to whatever seems the likeliest outcome, we can shape the future. Second, even in situations where things end badly—as life always ends, in death—fear is not a productive way to approach it.

In the face of such radical uncertainty, I like C.S. Lewis’s remarks about atomic bombs:

If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.

I recently walked past a funeral parlor where they had stenciled on the window a quote falsely attributed to Martin Luther: “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.”

I think this is the right attitude. Now is always a good time to make the future a better place by having kids, making art, anticipating and preventing harm, building companies, inventing things, and so on. If we do this, the worst thing that can happen is that we live meaningful and dignified lives. The best—given the trend lines we’re on—is unimaginably good.

Kafka's Diary - Sunday, August 2nd, 1914: "Germany has declared war on Russia. Swimming in the afternoon."

What a fantastic post Henrik!