Internet: a user manual

You can tap your fingers so that the world you live through the screen becomes a piece of art.

When explaining the internet to our five-year-old, Maud, I tell her that it is like an alien intelligence. We don’t exactly know what it is; it has just landed, and only the first few ships. We are still, as a culture, trying to figure out how this thing works. It did not come with a user manual.

The building blocks are simple enough. It’s just a set of rules that allow people to send and receive messages, create pages and link them together. But the thing that emerges when 5.16 billion people do this at the same time? That is the alien part.

People are spending, on average, six hours and 37 minutes a day pushing and pulling on this thing to see what it does. As with any exploration, this is not without its dangers. Many sustain injuries, mostly emotional in character: pressing the wrong bottom they become enraged, or they become polarized, addicted, confused, alienated, depressed, or turned into caricatures of themselves. Suicide rates are up among young users.

Some take these problems as evidence that this piece of technology is bad for us.

But that, I tell Maud, is like watching your little sister at the piano and from this conclude that the piano is a devil machine designed to produce arhythmical and migraine-inducing dissonances.

You can learn to play the internet well. You can tap your fingers so that the world you live through the screen becomes a piece of art. But it does not happen by itself; like the piano, it is a practice.

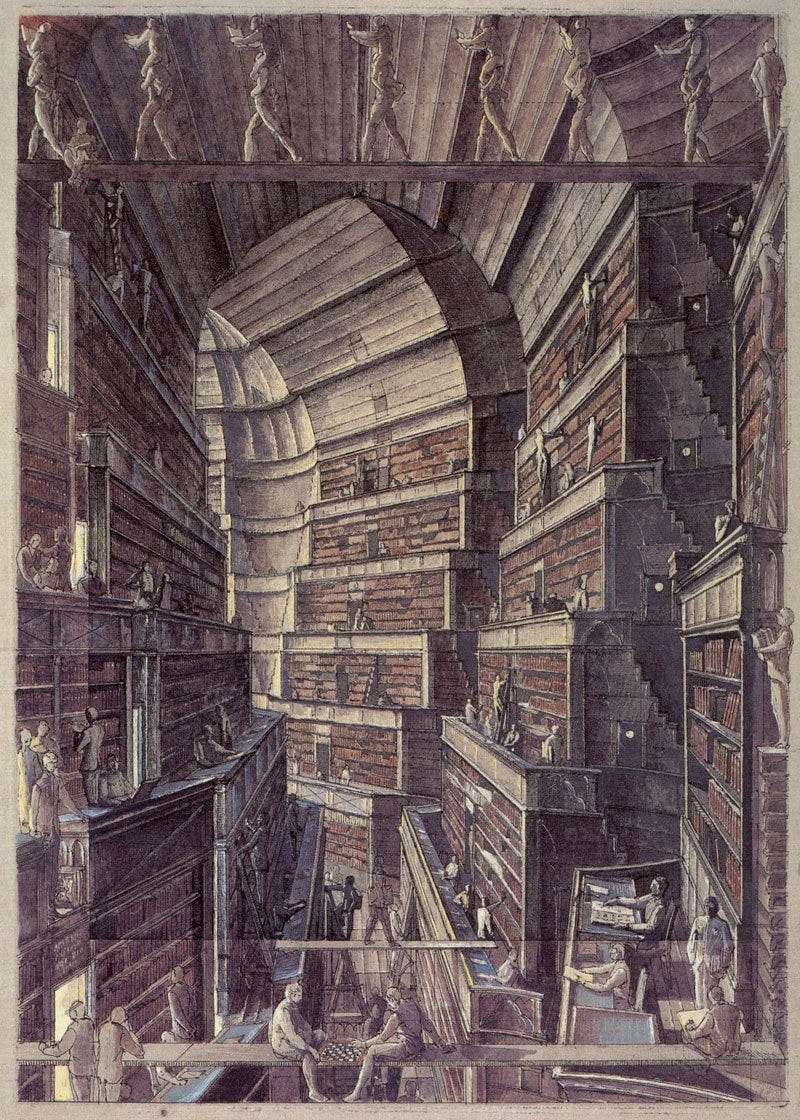

What is the internet? It is a stratospherically high pile of people and information, and a set of tools that lets you shake that pile into pretty much whatever shape you want. In other words: it is an instrument that lets you curate the world you live in. Instead of listening to an album, you can extract that one good song and let it flow into a playlist. Instead of spending the rest of your life with the people that happen to live in your village, you can poke the big internet pile until two hundred amazing people fall out and decide that that is your village, too.

Or you can shake down a social hell.

If you get better at the practice of shaping this world by tapping your fingers, the world you live in improves. Better information, better communities — and everything that is downstream of that. Work, friends, love. It is a virtuous cycle: spending your life in a better life-world will make it easier for you to expand your potential which will let you curate a better life-world still.

But used poorly, on the other hand, the internet will send you spiraling in the opposite direction.

Internet as practice

I find it useful to approach the internet as a practice.

A practice is more than just a thing you do; there is a structure around it, which helps you focus your effort. People who are serious about a sport, treat it as a practice. They have rituals that put them in the right state of mind (going to the gym, changing their clothes, etc). They have skill models and other types of social support. Mike Tyson, when training to become a boxer, would spend his spare time hunting for recordings of famous boxing matches he could watch with his housemates, all of whom were boxers living with their manager. In a practice like this, you have an idea of what excellence means, which you can measure yourself against.

What a practice means for the internet is a bit harder to define, since it is such an open-ended activity. But for me, I’ve found it useful to only use the internet when I’m sitting in my study — as if I was going to the gym. Something about climbing the stairs, walking past the bookshelves, and sitting down at the desk shapes my expectations such that my values become salient. I also start each session by looking over my notetaking system, where I keep lists of projects, problems, and questions I’m working on and where I journal.

Other people might not need as much deliberate structure, but if you want to have a productive relationship with the internet you should at least know what you are trying to achieve. Knowing your goals and values gives you something to calibrate against, so you know if what you are doing on the internet is summoning a world that supports you in those aims. If you do not have that clarity, there are other people who will fill that void; they will gobble up your attention and use it for their aims.

Having clarity around your goals is important for another reason, too.

Your goals shape what you notice and what you learn

You might have experienced this if you’ve ever looked for a friend in a crowd: suddenly, you notice the faces that otherwise would have been a mere background blur.

In the context of research, Robin Hanson talks about this goal-driven attention as chasing your reading. If you want to get more value from the books you read, you need to have a goal with your reading — a question you are trying to answer, a problem you are hoping to solve. This applies to using the internet as well, and it applies beyond research. If you go on Twitter looking for ways to contribute to friendly conversations, you will be primed for tweets where you can provide good replies. If you’re on Instagram looking for support in your project renovating a 19th-century door, you will end up in worlds dedicated to that.

Inversely, if you consume information because it seems vaguely interesting or because it was recommended to you by an algorithm, your mind will treat the information like the faces in a crowd when you’re not looking for a friend. You might remember a few shocking and strange sights, perhaps, but the vast majority of it will be gone forever when you turn to leave. Recent research suggests that when browsing social media people tend to experience what’s called “normative dissociation”, meaning they become less aware and less able to process information, and often can’t recall what they just read.

If, on the other hand, you have clarity around your values and the problems you are working on, you will see possibilities in the things that pass you by serendipitously. You will know what parts to skim and what to read closely. And you also have somewhere to store what you learn — in the mental structure provided by the questions and problems you are wrestling with.

Another benefit I notice when I have clarity around my goals is that I tend to be more critical of what I read when I measure it against a problem I am trying to solve. It is much easier for me to fool myself about things I do not have a direct effect on, like politics, compared to the stuff I do, like tending our garden.

The sum of this is that you will be able to make better decisions and extract more value if you know what you are trying to achieve, or at least what you value. Do you want to be a better parent, a better writer, a better friend? Having those goals, or values, front and center give you something to orient your internet use against. Then you can add whatever support structures and rituals help you keep that in focus, crafting a practice for yourself.

Repeatedly block the things that least serve you

Whenever I feel like something I did on the internet was a bad use of my time, I block it using a page blocker. This frees up time and space where the things I value can grow.

I used to be more sophisticated about it. I would come up with rules for when I could or could not do certain things. Things that felt like a waste of time when I was working might be ok when I’m tired, for example? I would decide to limit my use of Facebook to the evening, when I was too tired to work anyway, and didn’t feel like reading or going out in the yard to go look at bats killing dragonflies. That way I got to keep the pleasure that scrolling the news or binging YouTube clips gave when I was too tired to do anything better.

The problem with this was that this option was mostly fake. If I decided to do it a little in the evening, I was in fact deciding to do it more than a little and not just in the evening. The real options I had were two. Do it more than I want to. Or don’t do it at all.

At first, when I decided to not do a thing at all, there would be a temptation to revert back (to unblock the news and see if something interesting had happened, for example) but after a few weeks . . . I simply forgot about it. I would have found something else to do, like writing essays and emails to my friends, and now that occupied my time instead.

We don’t like to be bored, so we fill our time. If you remove all the things you don’t want to fill your life with, then it will fill with the good stuff. Sometimes the good stuff is just silence.

You can do this recursively. Prune the ten worst-used hours of your week, then prune the worst ten hours of what is left, until the most sustaining parts have grown to fill it all.

If this pruning of habits is hard, there is an endless amount of advice about breaking habits one search away. Search for it.

Blocking. Pruning. Blocking. Pruning. You can apply this idea at every level. If you are happy with your use of YouTube, except for cat videos which are a bit too addictive for you, then you click the three dots that appear when you hover over the name and tell YouTube you’re not interested. If you’re happy with your use of Twitter, except sometimes people write things that make you feel anger, anxiety, hate, or whatever feelings you want to avoid training yourself to feel — then you block them.

I pruned for many years. Now I rarely need to anymore: the stuff I truly enjoy at the deepest part of my being has grown so strong that I can’t be bothered with anything else. If I’m too tired to do meaningful work, have conversations with my friends on Zoom, read books, exercise, or hang out with my wife and kids — then my eyes, well, they fall shut and I snore.

That’s my practice.

There’s a lot more to using the internet than knowing what you want and avoiding the things that keep you from that. In the next part, which will be out whenever I feel like editing it, I will talk about how you find the good stuff.

See also:

A blog post is a very long and complex search query to find fascinating people and make them route interesting stuff to your inbox

I was born in July 1989, which means I am of the last generation who will remember the time before the internet. The cables and data centers and hyperlinks grew up around me; they grew with me. I find it hard to disentangle the evolution of my psyche from that of the internet.

This is so insightful. Not only did your fluid way of writing suck me in, the idea is also beautiful.

Sometimes, more stress comes from not knowing what we're after, not knowing what we want. We chase the wind and return wasted. Seeking purpose is good advice.

Brilliantly written and beautifully read. Loved this. I've been thinking lately about the idea of having an ecology of practice in which your routines and systems are coherent with your sense of self, aspirations, and external everyday constraints and this view of a practice fits really nicely - The Internet is a useful tool in the hands of the master, but it takes a self-awareness and deliberateness to learn how to wield it wisely.