There are certain works—paintings, films, books, gardens—that have an effect on me that I can most simply describe by saying: in their presence, I remember that I am a human being. Dry shallowness falls away. In this series, I write about works that have this effect on me.

This part is about the work of poet Tomas Tranströmer.

See also, part 1 about Herzog’s Into the Abyss and part 2 about Shostakovitch String Quartet no 8.

I.

Tired of all who come with words, words but no language

I went to the snow-covered island.

—Tomas Tranströmer

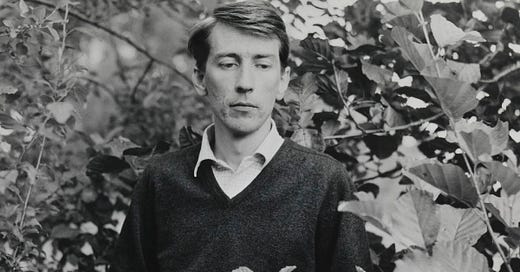

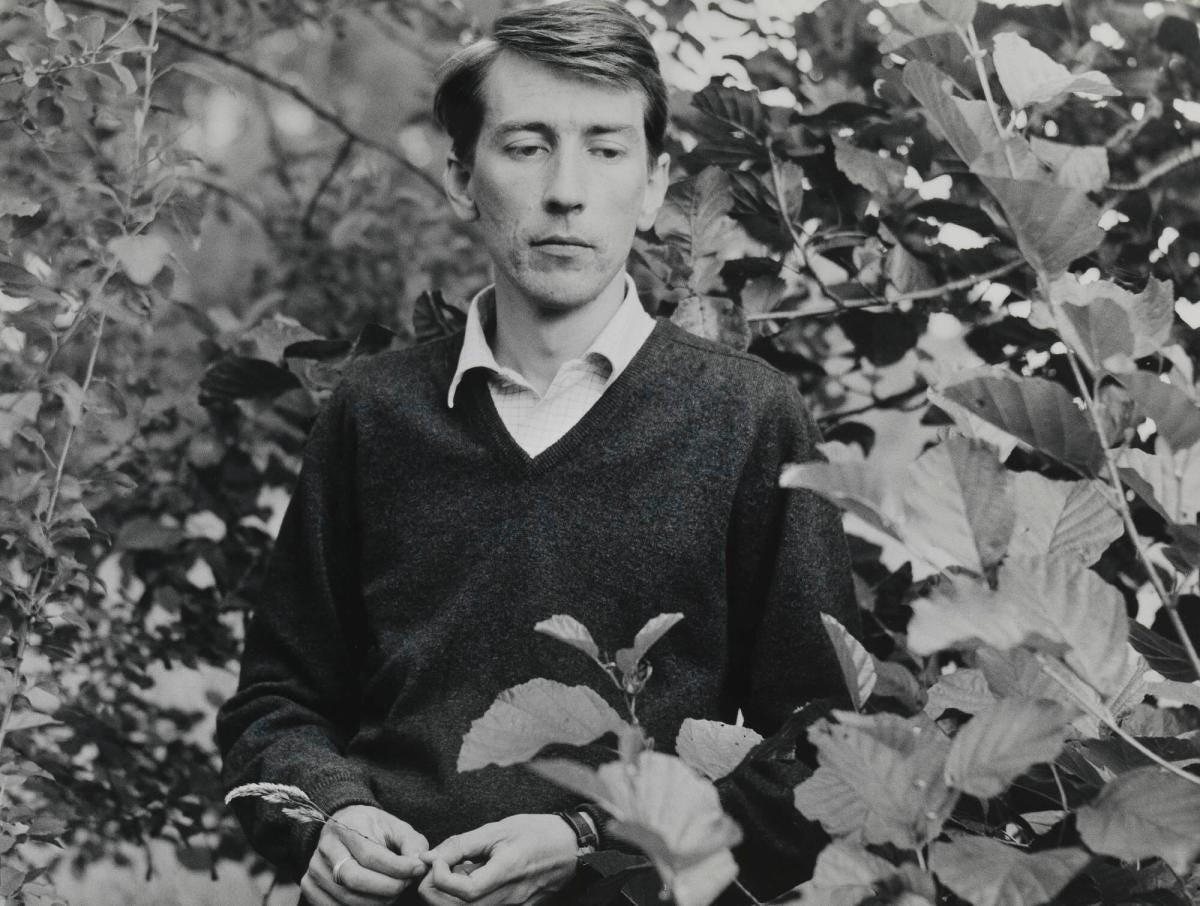

In 1954, when the poet Tomas Tranströmer published his first collection, reviewers hailed him as the most gifted writer of his generation. He was 23. You could sense forces rushing forth to prepare a path for him. There would be reading tours and residencies. He would be given literary grants and other support. In thirty years, when he had been groomed, they would induct him into the Swedish Academy to decide the Nobel prize.

But this path did not fit with Tranströmer’s sense of integrity.

Six years after his debut, he moved into a bungalow at the juvenile prison in Roxtuna. There, he would work as a psychologist, living next to the inmates in a secluded pine forest by the Roxen Lake. Tranströmer, who had grown up in Stockholm, attending Sweden’s most prestigious Latin high school, spent the rest of his life in small Swedish towns, away from the literary power centers.

II.

After his move, he fell out of favor with the literary elite. They felt he didn’t keep up with the times. In 1966, when he released Klanger och spår (Bells and Tracks), one reviewer called him a “used-up poet.” Used-up meant: he wasn’t political enough.

During the Vietnam War, literature in Stockholm was synonymous with politics (even more so than in other countries at the time, and more than in most quarters today). Writers staged a war tribunal in Stockholm where President Lyndon B. Johnson was sentenced in absentia for crimes against humanity. That sort of thing. Tranströmer, who attended the tribunal, wrote to the American poet Robert Bly: “It is one of those things that makes you feel like you have a crack through the top of your head down to the crutch.” And: “I’m not going to apologize for writing poems about blades of grass.”

Since Tranströmer felt alienated in Sweden, his social life revolved around letters to poets in other parts of the world. The poets found each other by circulating their work in letter networks and small magazines; their poems became search queries that surfaced people they could relate to.

The first letter Tranströmer and Bly shared is Tranströmer asking for permission to translate a poem he has read in The Sixties Press, the magazine Bly edited. Bly replies that he found the letter in his box the minute he returned from a 600-mile drive to Chicago where he had gone to locate copies of Tranströmer’s collections!

The letters to Bly often return to the war. They were both appalled by Vietnam. But Tranströmer (unlike Bly) was also appalled by many of the critics of the war. The critics were, in Tranströmer’s eyes, more driven by political intoxication than a care for the victims in Vietnam. The stated goal of an open letter Tranströmer was asked to sign was to create “a hundred Vietnams.” He wanted none. In one letter, Tranströmer quotes an op-ed by a friend from his days in Stockholm: the friend says he hopes the US will continue its bombings since it helps spread anti-American sentiments.

Being bothered by this was not something Tranströmer talked about publicly. But sometimes his poems gave him away. In “With the River,” a poem about a bridge across the Dala River, he wrote:

In conversations with contemporaries, I saw-heard behind their faces

the current

that flowed on and on and pulled with it the willing and unwilling.And the creature with stuck-together eyes

that wants to go right down the rapids with the current

throws itself forward without trembling

in a furious hunger for simplicity.

When “With the River” was published in the magazine Konkret in 1967, Tranströmer received a letter from the Writer’s Association informing him that Göran Sonnevi had reservations. Sonnevi was the leading Swedish poet of the 1960s. The letter was signed by Göran Palm—later a Tranströmer scholar—who seemed genuinely unsettled by the idea that he might be a creature that hungers for simplicity. The letter ended with Palm asking Tranströmer what he plans to do when the revolution comes?

There will be no comfortable social democracy to lean your head against when the river gets violent enough and only the political extremes remain. . . if there is a right-wing coup, no one is going to care about your capacity to see . . .

Tranströmer was uneasy with the reactions to his poems, and he kept a low profile. In a survey in 1968, he was asked what had caused the left turn of the cultural sector in the 1960s. Tranströmer (who was himself left-leaning) wrote an answer but didn’t publish it:

1. The obvious world-historical conditions: the thawing of the Cold War and the shift of attention to the Third World around 1960. The increasingly brutal foreign policy of the United States in the mid-60s[.] Above all, the Vietnam War as a point where the divided left could unite and be joined by an opinion that is not otherwise ‘left’. When this happens, a pressure wave arises that moves the entire public opinion a step further.

[…]

4. The need for faith. I mean this partly in religious terms. The Swedish intellectual milieu is one of the most secularized in the world. And when the path to religion in the traditional sense is blocked, the religious needs will seek outlets that are accepted: right now, for example, in left-wing ideology. But also on a non-religious level, there is a need for faith: a desire for simplicity, fixed norms, an infallible method of analysis. The increasing flow of often contradictory information in a changing world makes the need for a fixed structure of thought, an apparatus for sorting and evaluating the information, extremely strong. When disoriented enough, the leap to an ideology is experienced as a moral salvation and a boost of strength.

[…]

8. The Swedish cultural elite is small. When a tendency begins to prevail, it quickly gains almost total dominance.

I’m a bit vary including this quote. It makes Tranströmer sound like the type of person who, had he been alive and on Twitter, would have published threads attacking wokeness to boost his follower count. He wouldn’t have done that. He would have written poems about insects he found at his summer cottage. Then he would have sent them to his friends in a private chat group.

III.

Here is a poem. It is called “Schubertiana,” after the composer Schubert. It was written in the early 1980s after Robert Bly had invited Tranströmer to do a reading tour in the US. Pulling the car over at an outlook, on the way into New York, Tranström notes (in Patty Crane’s translation):

The giant city over there is a long flickering snow drift, a spiral galaxy seen from the side.

Within the galaxy, coffee cups are slid across the counter, storefront windows beg from passers-by, a swarm of shoes that leave no tracks.

The climbing fire escapes, elevator doors gliding together, and behind doors bolted with police locks, a steady flow of voices.

Slouched bodies doze in subway cars, the rushing catacombs.

Seen from this distance the city becomes statistics; what is human is lost. But Tranströmer also knows “—without statistics—that right now Schubert is being played in some room over there and that for someone those notes are more real than anything else.” The music, in the following stanza, is described as somewhere you can “curl up like a fetus, fall asleep, roll weightless into the future, suddenly knowing that the plants have thoughts.” It captures “the signals from an entire life in some rather ordinary chords for five strings.”

All of this could be said about Tranströmer's work, too. It is small and personal—it fits in a volume slim enough to fit in my pocket. But when I open it: vaults open behind vaults without end, to borrow a metaphor Tranströmer used for the human soul.

This humble humanness was what his critics called "used-up." But those who said so rallied around Pol Pot during the Killing Fields, when at least 1,386,734 victims were executed.

The final stanza of “Schubertiana,” seen in this political context, reads like a summary of Tranströmer's work:

Annie said “this music is so heroic,” and that’s true.

But those who keep an envious eye on men of action, those who deep down despise themselves for not being murderers,

they don’t recognize themselves here.

And the many who buy and sell people, believing everyone can be bought, don’t recognize themselves here.

Not their music. The long melody that remains itself in all its transformations, sometimes glittering and tender, sometimes harsh and strong, snail trails and steel wire.

The persistent humming that’s right now following us

up into

the depths.

In 1991, at 59, Tranströmer suffered a stroke that robbed him of speech. As his poems became acclaimed abroad, translated into more than fifty languages, the Swedish literary elite dropped their criticism and embraced him. In 2011, he was awarded the Nobel prize. On 26 March 2015, he passed away.

My favorite book by Tranströmer is Baltics which can be read translated in its entrity here—it is only slightly longer than this essay. Though of course denser: it took him five years to write. I’ve read it at least a hundred times. But really anything by him is worth reading.

Of the English translations, Patty Crane and Robert Bly usually comes close to the original.

I also recommend this recording of a reading Tranströmer did at Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room in 1981. The recordings from Woodberry Poetry Room is a treasure trove in general. It really adds something to hear the timbre, personality and cadance of a poets voice.

Into the Abyss

There are certain works—paintings, films, books, gardens—that have an effect on me that I can only describe by saying: in their presence, I remember that I am a human being. Dry shallowness falls away. I’ve been playing around with the idea of making a series where I share works that have this effect on me, along with a short essay explaining what I see in them. It would be something like a small treat in between the larger, more time intensive essays I write. Let me know if you would enjoy that. Here is a trial.

Yes to more examples of people sticking to their rhythms, creative inspirations and ambitions for life! I love how Tranströmer did not follow the path that was being laid out for him and instead wandered away from the literary power centres to do his own thing.

I recently found an interview of the American author Donna Tartt with the CBS News in which she said she would be happy writing five books in her lifetime because she writes at a devastatingly slow pace (a decade for each of the three books she has written). Her debut novel, The Secret History, was critically and commercially successful (not to mention, long). She could have tried to write a liiitle faster, but it made her unhappy so she's content with writing two more. Love when people do things that make no sense in the present but turn out to have payoffs in the long run.