How I write essays

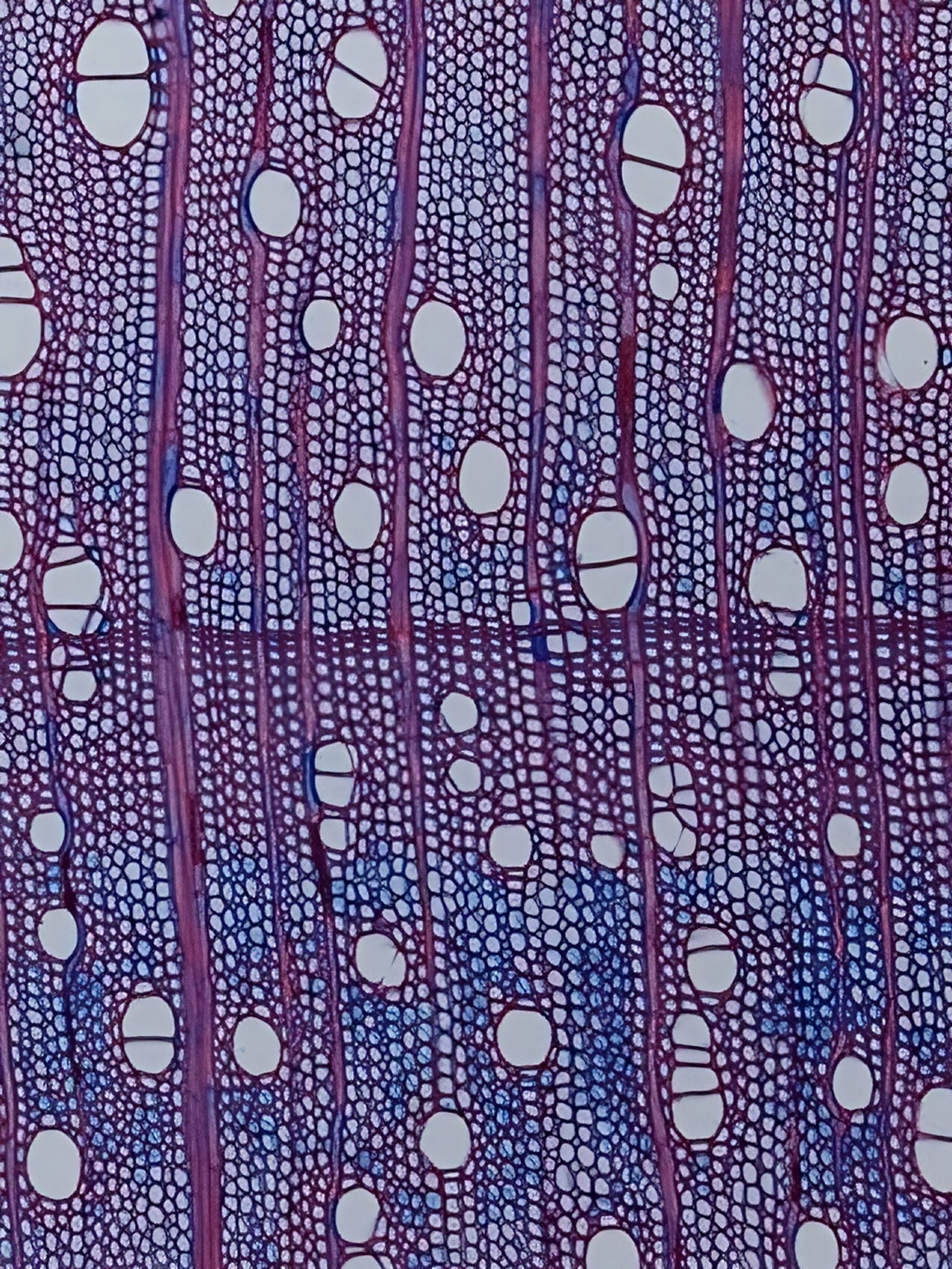

Microscope image of wood tissue

On 24 September, I wrote in the waste book about how I created the essays I’m most happy with. I was looking for patterns in my processes (and how the processes behind the good essays differed from those that led to the many mediocre essays I’ve written over the last 3.5 years).

The idealized version of how my better essays were written looked like this (abbreviated):

I spend plenty of time reading, talking to interesting people, and writing in my notebooks. (Starting essays before I have deeply internalized an idea does not work for me.)

When I get excited about something, I articulate that as an “animating question.” In this post, it is, “How do I write good essays?” (Without that, the material is just a lump, and reading it feels like drifting.)

I collect my thoughts in a wild sprawling mess. I have one or two million words in my journals and notes: I surface the relevant parts and throw them into a shared document.

In this mess, I look for recurring topics and ideas. I rearrange the thoughts so that I get a few strong, separate ideas. Then I prune tangents that don’t fit those clusters.

I make a guess about what order to deal with the points. This is not a blueprint, but a prediction.

Without looking too much at my blueprint, I write the core part of the essay from “top to bottom.” I do not write an opening, nor an ending. I do not pick a narrative material—I let whatever occurs in the draft occur, for now.

I reread the draft and pay attention to any strong ideas or narratives that emerged organically. I strengthen them, and prune the weak ones. I move things around if it creates more movement or stronger centers.

Now, I write the opening and the end. The goal is to strengthen the whole and make it feel coherent.

I edit until I can’t find any more ways to improve it (or run out of time).

(Notice that this sequence describes creating essays—which are like amulets to me, encapsulating important insights, so I can return to them in my head, or reference them in conversations with friends. If I just want to think about something, I write in another way.)

Strategy and process is mostly a mistake when doing creative work

After I wrote the list above, I wanted to see what would happen if I systematically followed the process. That was 2 months ago. I have now written six essays using the process. To sum up the experience: that list of steps is a good first approximation of what works for me. It avoids many pitfalls that I typically fall into. But to honor the potential of the material I am working with I almost always have to break out of the process and get lost in the desert.

Having a method, a process, makes my writing more consistently good. This might sound like a win, but it is a problem. The usefulness and beauty of essays follow a power law, where the outliers create almost all the value—so if I make my essays more consistent, I remove not only the mistakes but also much of the upside. A method can, if used wisely, be a tool that helps you see possibilities. It can’t replace paying close attention to the material and figuring out what it is asking of you.

As I was exploring this, I kept a writing diary. What follows is ~3000 words of reflections based on those notes. (See also, “How I wrote ‘Looking for Alice.’”)