Sometimes the reason you can’t find people you resonate with is because you misread the ones you meet

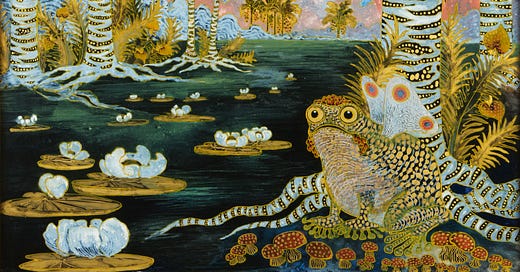

“Through a Glass Lushly,” Michalina Janoszanka, ca. 1920

1.

Sometimes two people will stand next to each other for fifteen years, both feeling out of place and alone, like no one gets them, and then one day, they look up at each other and say, “Oh, there you are.”

In the early 2000s, Helle (who is the daughter of two of my friends) was at Copenhagen University. Helle and some classmates decided to meet up each Thursday for dinner. As the months went by, one person after the other found a partner, got busy, and stopped coming, until only Helle and one of the men were left. They, on the other hand, were surprisingly stubborn: the year they turned 41, they were still having dinner every Thursday. That year, Helle had no one to travel with, so she asked the man if he wanted to come along to Greece, and, spending a week together on Milos, they realized they loved each other.

“A little too late for any grandchildren, though,” said Helle’s mother, Alice, when she told me the story.

If you’ve never changed your mind about a person like that, it might sound like Helle and her husband were exceptionally out of touch with their feelings (or perhaps they settled once they ran out of options). I don’t think that was the case. I’ve met them a few times, at and after Helle’s mother’s funeral, sadly, and they seemed like sensible people and a clear match. I wouldn’t be surprised if it is rather common for people to misread each other like that, except, most people never get around to realizing their mistake.

Maybe I’m projecting.

2.

The story I really wanted to tell in this essay is about Torbjörn, who is one of my two closest friends, but who spent 15 years as one of the extras in my life before I realized he was one of the main characters. I suspect there are a few important lessons to be learned by meditating on how it was possible for me to misread an opportunity for genuine friendship for so long.

The embarrassing thing is that I don’t remember when I met Torbjörn. I know for a fact that we were at the same middle school, but when I’m picturing him there, I’m pretty sure I’m constructing false memories. Three years later, though, we entered high school, and since that time, I have real memories of him.

We were in a class that did extra math and programming, and the social dynamic had a strong impro theater feel to it. You basically never talked as yourself, you were always switching in and out of characters, in an attempt to make the others laugh. (To this very day, I always pretend to be someone else when Torbjörn calls me, as does he.) And, not to put anyone down, but Torbjörn was better at this game than anyone else. He was so fast and exceptional at reacting to what someone else was saying in a way that made it twice as fun. He was sort of a shy guy, but when he got excited, as he often did, he would talk so loud it sounded like he was screaming, and then there’d be a moment when he realized what outrageous stuff he was screaming, looked around himself, and blushed. I had to crawl out of the corridor because I was laughing so hard sometimes.

However, it was a type of fun that I preferred in small doses. I was the kind of kid who preferred to hang out in the school library and read the plays of Harold Pinter, or sneak off to the abandoned church-turned-furniture store that me and seven other musicians had converted into a rehearsal space. I felt like I belonged out in “the real world,” in the city. Torbjörn came from even deeper into farm country than I did, listened to Rammstein, drove an orange Volvo 240, and seemed at peace with that.

3.

Aristotle has a famous passage in the Nicomachean Ethics where he talks about different types of friendship, and I think what he says there can explain, at least partly, why I misread Torbjörn.

There are three types of friendship, Aristotle says. The first one is based on pleasure—the way our relationship in high school was all about laughing, or the way you can date someone because they are hot and make you feel good. The second is based on utility—you’re friends because it is useful, because your friend plays drums and you need a drummer in your band, or you’re friends because the other person is high status and gives you access to resources (though, that is a little embarrassing to admit so you lie to yourself and say that the reason you like them has nothing to do with status hunger).

Looking back, I was heavily oriented toward friendships of utility as a teenager. Most children are self-centered like this, and I think that is probably healthy: you need people to help you out into the world when you are young, people who can help you grow. In my case, what I was (subconsciously) looking for were people who were active and extroverted and who could help me get over my natural shyness and break out into the world. And I wanted a band.

Torbjörn wasn’t useful in any of these pursuits, and I wasn’t yet mature enough to see the value of a person irrespective of the value they could confer to me. Hence, he became an extra.

The third and deepest kinds of friendship, according to Aristotle, are friendships of virtue. That is, you like a person because of their character. They might be fun, they might be useful, but even if they aren’t, you like them anyway. It is what the marriage vows are getting at with the line: “To have and to hold, from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, till death do us part.” Is this the kind of person that, if they were old and ugly and had soiled their pants and needed your help, then you’d still say, Yes? “Yes, I would love to. I want to give this person my care so they can unfold their life with dignity.”

That is a friendship of virtue.

And in a long enough perspective, it is the only thing that matters in a relationship. Pleasure will come and go, as will utility. You can’t build a long-term, full-bodied relationship on that. If you are dating someone because they make you feel excited, and then the hormonal swing caused by the crush balances back to normal, then there isn’t much left. If you are friends with someone because they are as obsessed with poetry as you, and then you lose your interest in poetry, then you’ll likely stop hanging out.

That is what happened to almost all the people I was friends with during the years I misread Torbjörn: we crossed paths, were useful to each other, and then stopped hanging when our trajectories no longer intersected.

Happiness and utility are like short-term fluctuations in the stock market. They come and go. But if you zoom out long enough, you see that there is a deeper, slower force working under those short-term fluctuations, and that is what really matters. The thing that Aristotle is gesturing at when he talks about friendships of virtue is like that. When two people come together in mutual care for each other's character, in good times and bad, that is what changes everything in the long run.

I was too young to see that when I first met Torbjörn, though. I only saw the short-term fluctuations.

4.

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

—Marcel Proust

A decade passed.

I left the small town we lived in at 18, I left as soon as I could, the same week we graduated. Two years later, I was renting an apartment on Pine Street in San Francisco with my then girlfriend, and, even though I could only bear SF for two months, I saw myself as that kind of person. Back in Sweden, I was pulled into the literary scene in Stockholm. Reading poems in bars: that felt like real life to me.

Then, almost as quickly, it felt like an empty status game and bored me. At 25, I soured on literature and turned to math and programming again.

Around this time, my brother and I ran into Torbjörn at a mutual friend’s apartment, where we all regressed into the dynamic we had had as 17-year-olds and made improper jokes for a few hours.

Torbjörn was, as I knew, working as a software consultant in the precision tool industry. I asked him if I could call him to get his thoughts about some software engineering stuff that I was struggling with. (Utility is as good a place as any to start a friendship.)

I took the train out to the apartment where he lived with his now wife, M, and we talked for several hours while walking in circles on the lawn. (It was M, laughing at us from the window, who pointed out later that we walked in circles, we were too immersed in conversation to notice.)

Almost right away, I realized that I had misunderstood him.

5.

I had thought of him as funny, but that wasn’t what he was. What he was was responsive. He was fully attuned in any conversation he had. He heard what the others were saying in a way that few people do, and could, without missing a beat, wring out a genuine and fitting thought from himself. Like the impro stuff, but for everything.

In the context of a large group, where you want everyone to have a good time, this responsiveness took the form of playing dexterously with the lowest common denominator, which was humorous riffs on shared memes. But hanging 1-on-1 (which I now realized I had never done with him before) that same responsiveness meant locking into each other in that exhilarating way where you finish each other’s sentences and get to the heart of things.

Torbjörn has always had a tenuous relationship with the written word, that is to say, he barely reads. But if I get obsessed with, say, the history of Polish literature, as I’ve been for the last few months, and he asks me about that, and I start to tell him about some insight I got from reading Tadeusz Konwicki, he’ll break me off mid-sentence and scream, “…AND THAT MEANS THAT XXXX, RIGHT?” Where XXX is whatever insight I have extracted from the bowels of the earth and had meant to share with him.

That responsiveness is Torbjörn’s core virtue. He’s attuned, he’s there. And he’s kind, and he’s funny, and he has such a beautiful soul that I want to see bloom.

6.

But as obvious as this seems to me now, I failed to see it for 15 years. I had only seen him in one set of contexts (at school, among our friends), and I had assumed that the mental model I constructed of him there was who he was. But it wasn’t. I missed the whole thing. And I needed to change how I approached him to see how much I had missed.

My mistake was twofold.

I was focused on a superficial level, looking for friends who shared my interests, instead of paying attention to the deeper structure of their personality: the way they process the world, their values, and virtues. Which, to be fair, takes more life experience to perceive than superficial compatibilities.

I didn’t sample data broadly enough. I observed Torbjörn in one context and thought, “He’s that kind of guy,” instead of thinking, “He seems like that kind of guy, now let’s throw him a curve ball and see what happens.” I could have asked him different sorts of questions, could have invited him to other types of contexts, and I would have gotten a more rounded and true feel for him. I don’t think it is a coincidence that Helle and her husband figured out that they had misread each other in Greece, and not in the midst of their normal habits of life.

This lesson dovetails with the point I made in “Dostoevsky as lover,” about the early days of my relationship with Johanna:

A person can’t be contained in your ideas about them. This was a core idea for us. To whatever extent I assumed I knew who Johanna was, I treated her as something that I could fit in my head — as something smaller than me. But she couldn’t fit in my head, nor I in hers: that was the exciting thing about it. You can only ever know another individual if you meet them in open dialogue — if you treat them as unfinished, as capable of surprise.

If someone seems boring to you, or a bad fit, it might be that you don’t know how to prompt them, that you haven’t seen them react to the context that brings out their full being. You probably don’t know how much beauty lies hidden in the people around you.

Thank you, Esha and J, for comments on the draft.

This is too real

This was beautifully written, thank you! I love the notion of misreading people; I think it's such an important trap to be aware of.