This essay is the first of a series. Here is part 2, part 3, and part 4.

Once you see the boundaries of your environment, they are no longer the boundaries of your environment.

Marshall McLuhan

The inside of a womb looks as it did 70,000 years ago, but the world outside has changed. In July 2021, when our daughter was born, the night sky didn’t light up with stars; it was lit up by the warm afterglow of sodium street lamps. Green-clad women carried the baby away, pumping oxygen into her mouth. It was like something out of a sci-fi: she had woken up, without a memory, in an alien world. Smeared in white-yellow fat, she didn’t know who she was nor what she was doing here. The only thing she knew, genetically, was that she needed to figure this out fast or die.

How do we ever do this?

Chimpanzees, who are born into the habitat their genes expect, get by largely on instinct. We cannot. We have to rely on what anthropologists call cultural learning. We have to observe the people that surround us; we have to figure out who among them navigates our local culture best and then extract the mental models that allow them to do so. This is a wicked problem. But we solve it instinctively. It is the main thing that sets us apart from chimpanzees.

As I wrote in Apprenticeship Online:

If you measure two-and-a-half-year-old children against chimpanzees and orangutans, they are about even in their capacity to handle tools and solve problems on their own. Only when it comes to observing others and repeating their actions is there a noticeable difference.

Two-and-a-half-year-olds can extract knowledge from people just by watching them move about a room. They start to desire what those around them desire. They pick up tacit knowledge. They change their dialect to match their peer group. And after a handful of years of hanging about with people more skilled than themselves, our babies—these tiny, soft-skulled creatures—can out-compete chimpanzees in all but close combat.

This ability is not something you can turn on and off. You are always internalizing the culture around you. Even when you wish you didn’t. So you better surround yourself with something you want inside—curate a culture.

Your culture shapes who you become

How do you summon an interesting set of friends to bounce your ideas off? Where do you look to find good influences? Which types of output should you produce if you want people to route useful ideas your way?

This essay is the first in a series about culture curation. In later parts (which I will send out to subscribers during the fall), I will go into detail about how to do this. But here I want to give a high-level view of why it makes sense to think about the world in this manner—as a graph you can restructure to change yourself. Why should you put effort into shaping your culture, rather than something else?

Here is a reason. Over the last few months, I’ve been reading about 30 biographies on the upbringings of historical geniuses (for an upcoming post). What has struck me, more than anything else, is the quality of the cultures they internalized. The pedagogies their guardians employed differed radically; they had differing temperaments; they mastered different disciplines, but they all had this in common: they spent their days around highly competent people.

Most who grew up to become geniuses, pre-1900, were kept apart from same age peers and raised at home, by tutors or parents. Michel Montaigne’s father employed only servants who were fluent in Latin, curating a classical culture, so Montaigne would read the classics in his mother tongue. J.S. Mill spent his childhood at his father’s desk, helping his father write a treatise on economics, running over to Jeremy Bentham’s house to borrow books and discuss ideas.

Blaise Pascal, too, was homeschooled by his father. His father choose not to teach him math. (The father, Etienne, had a passion for mathematics that he felt was slightly unhealthy. He feared mathematics would distract Pascal from less intrinsically rewarding pursuits, such as literature, much like modern parents fear TikTok.) Pascal had to teach himself. When it was discovered that Pascal, then a young teenager, had rederived several of Euclid’s proofs, the family relocated to Paris so father and son could participate in the mathematical salons of Mersenne. The instinct was to curate a culture, not to teach, not primarily.

By replacing a peer group that is low-skilled (such as a peer group in a school) with one that is exceptional (such as Mersenne’s mathematical salon), we can leverage our human capacity to internalize our culture to foster exceptional talent.

No, it is your milieu that shapes you

I’ve been using the word culture so far, but that is not the exact word for what I am gesturing at. It is not the wider culture we internalize; it is the particular set of influences that surround us, what Tim Urban has called “our unique cultural intersection”. Is there a word for this? I don’t know. But discussing the terminology with GPT-3, a large language model, it suggests I use the word milieu, which sounds sophisticated in a distinctly French way. This I can live with.

A milieu, says GPT-3, is the culture contained in your unique set of connections. (Merriam Webster’s dictionary says “the physical or social setting in which something occurs or develops”.) Unlike the word culture, as anthropologists invoke it when they talk about “French culture” or “Balinese culture”, a milieu is not a monolithic thing. Your milieu is not the same as your sister’s. It is an ever-shifting, individual configuration of information flows. The Twitter feed you have curated is a milieu. Your friend group (which is not the same as the friend groups of the other people in that group!) is a milieu.

It is by changing your milieu that you change yourself.

Curating our milieu is something we all do these days, if not always consciously. Our milieus are no longer determined by where we were born, but by our choices of friends and careers, and, increasingly, by how we train the algorithms that feed us content. Most of us have not yet developed the know-how to fully leverage this.

How can we do that?

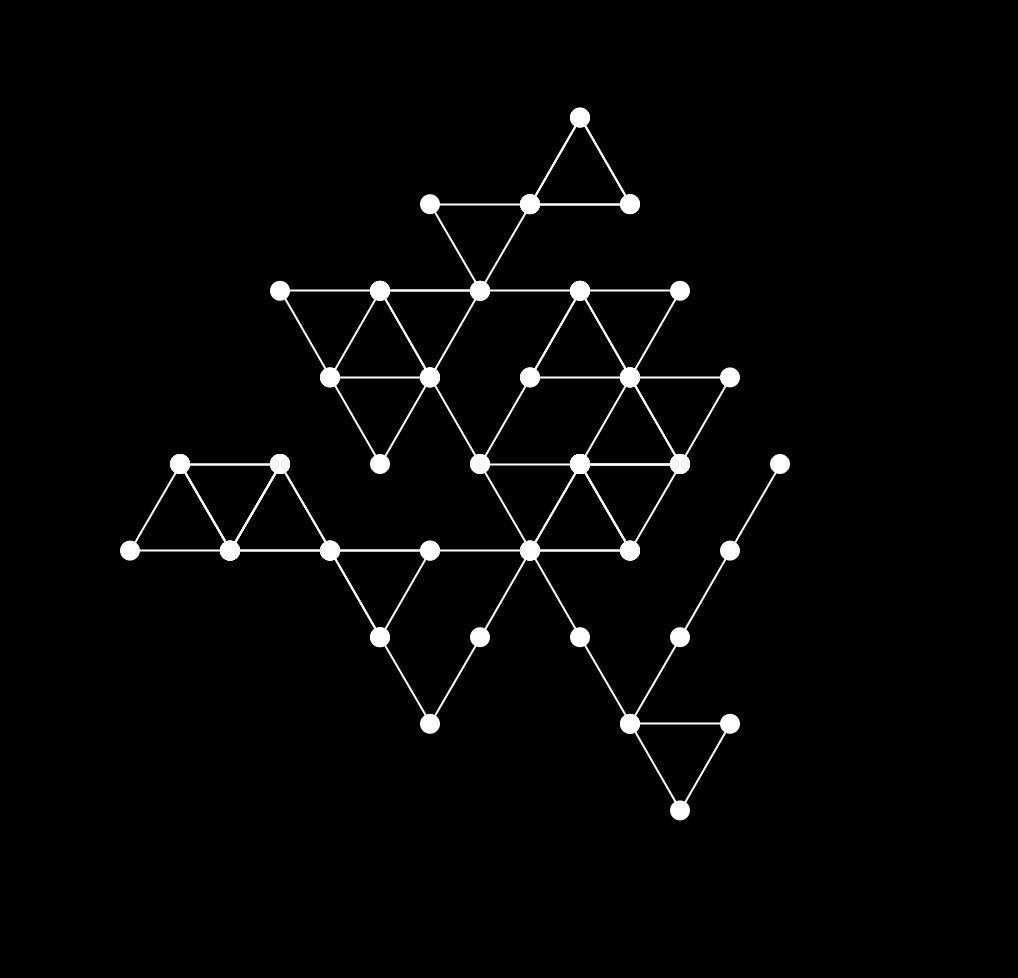

A milieu is a directed graph

Before we can answer that question we need a model so we can visualize what we are talking about.

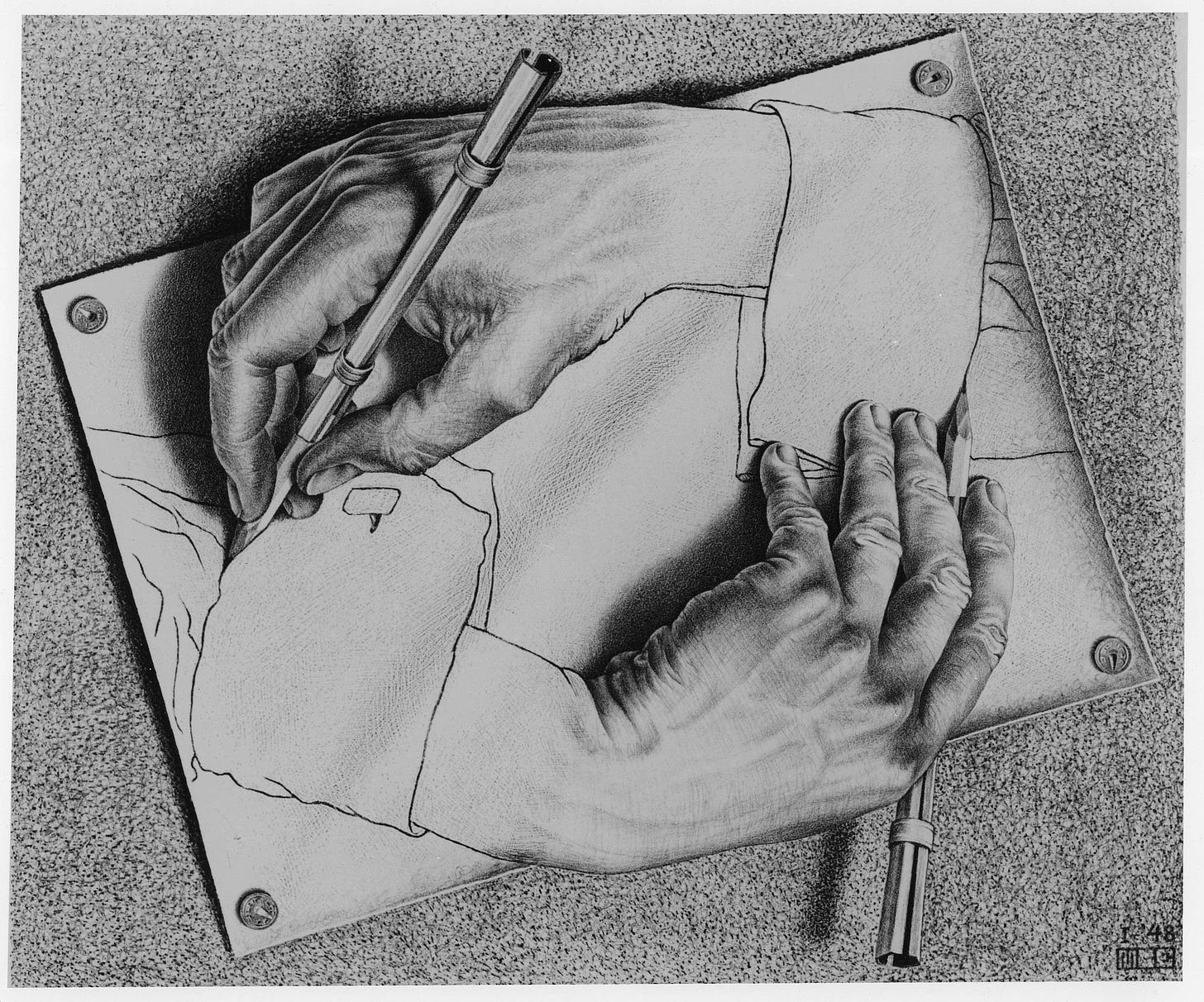

The milieu around you—which shapes you, and which you shape in turn—we can model as a directed graph. The nodes are people and objects and ideas connected to each other. And the graph is directed because you have nodes that send you input and nodes you send output to.

Books you read are sending you input. Your friends modeling behaviors for you. Newspapers. Tools. People you follow on Twitter. The architecture of a Gothic church beaming serenity into you—that is input too.

At the same time, you are also sending output to other nodes. Now, I am sending these ideas into my pocket notebook, which will send them to my future self, who will send them to you—now. My five-year-old, watching me jot down the notes, my hands foamy from the dishes, is also an audience for my output, albeit the lesson she draws is another.

It is this overall flow, into you and out from you, that determines what you become. The more you think about this, the stranger the world seems. It is a bit like dropping a handful of magic mushroom in your teakettle: you cease to be a separate self, and become a part of the larger flow of things. This is the logic of the internet.

As Nadia Asparouhova writes:

If “grit” – the desire to persevere when faced with a challenge, popularized by psychologist Angela Duckworth – has been the human trait du jour of the last fifteen-odd years, I suspect that “agency” – a belief in one’s ability to influence their circumstances – could be the defining trait of the next generation.

Grit is the node’s eye’s view. You are struggling against the graph. Agency, on the other hand, is the view from the graph. You are the graph. By changing it, you are changing yourself.

Curating your input

Be careful what you read for it is what you will become.

—Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Last night, as I was falling asleep, the music producer Rick Rubin was beaming input into my lucid, semi-awake mind. He was interviewing John Frusciante. In the 1980s, Frusciante was a prodigal teenage guitarist who was drafted to Red Hot Chili Peppers when the band lost its first guitarist Hillel Slovak to a heroin overdose. Anthony Keidis, the lead singer of the band, remarks in the interview that what sets Frusciante apart as a guitarist is that he is uncommonly undistractable (“he can really focus and concentrate and apply himself to his craft in a way where the noise of the world has less of an impact”).

In the words of this essay, this can be rephrased as: Frusciante has an uncommon discipline about what he lets into his senses; he is uncommonly deliberate about curating his milieu. His mode of writing songs is to select a set of guitarists and play along to their recordings (“I'm playing along with music that I'd like to be influenced by”) until new ideas start to emerge. He arranges a constellation of nodes and channels the input they send him into new music.

Rick Rubin: What would you say your biggest guitar influences are? Can you answer that question? Is it too wide?

John Frusciante: Well, right now it seems like throughout making this record, the main people for me were Freddie King, Johnny Guitar Watson, Clarence Gape, Moth Brown. These are all electric blues players from the fifties and early sixties. And then Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix have always been big for me, but they were particularly big, especially Jeff Beck, while we were making this record. […]

I got to a point where I was realizing that what was happening in my playing was that I was trying to bridge a kind of a gap between someone like Jeff Beck, who has a lot of very interesting techniques that are very lyrical and expressive—making the guitar sound almost like it's a singer or something—it seemed like I was bridging a gap between that and someone like Kurt Cobain, who, especially in his improvisational playing, is not so much about techniques per se; it's about putting a lot of energy into the instrument and playing in a way that has reckless abandon.

Unlike my musician friends, who are just jamming and listening to whatever catches their fancy, Frusciante seems to have a detailed understanding of who his influences should be and why. He knows how their playing styles interrelate and where he wants to position himself in that landscape of playing. He has a map of guitarists. The map is organized by technique but also by the effect they have on him, the kind of songwriting they open up. He tweaks this web of influences to change his playing.

This skill , though less obvous than his considerable technical skills, help set Frusciante apart as a guitarist and songwriter. You see the same pattern with top performers in many domains—researchers, programmers, painters. Often they spend a great deal of thought on how to structure their milieu: whom to interact with, and what work to study and learn from. You can do this for soft values too, training yourself to be generous by surrounding yourself with generosity, for example, or getting perspective by spending time with the dying.

What you allow your milieu to feed into your mind is what you will be processing. It is what will carve the pathways of your brain. This is perhaps well-understood, in theory if not in practice.

But it is equally important to consider who and what you are sending output to.

The gravity field of your “audience”

For a few years in my early twenties, I passed myself off as a poet. I could recite Tomas Tranströmer’s collection Baltics in its entirety from memory, and when one of the directors at the Royal Dramatic Theater took me under his wings, teaching me how to move an audience, I started getting a steady stream of invitations to read my verse.

These one hundred or so recitals had a powerful effect on me. I had a tendency to model the preferences of my “audience”, which I think is quite common, whether in everyday interactions or on stage, and knowing those preferences, it was hard not to shape myself to fit them.

In the split second before speaking, we project ourselves into the position of our addressee, imagine how they will take what we’re about to say, then adjust our communication to fit those expectations. This mechanism, performed in milliseconds, leads us to utter not what we’d intended, but an edited version that accounts for—protects against—the ways that the psychic representation of our addressee thinks and feels.

Since I was constrained by my stanzas, I could not do this millisecond correction to fit my words to my audience’s expectations. Instead, I had to wander far out into the space this correction is normally protecting us from. I would reveal my innermost thoughts and stare into the mouth of a woman yawning. People would quietly get up and leave mid-sentence—and I would have to finish it.

Over time, I got good at modeling these reactions ahead of time. This changed my writing, and it changed me. I became shrewd-cute and the writing became not a line of words on paper but an instrument to manipluate my audience. This shaping is not bad in itself. The problem was rather this: the gravity field of this particular audience did not align with my ethics and aesthetics: their expectations pulled me away from the places my thoughts needed to go. The poems, in conforming to their laughs and tears, hollowed out.

To write what I was meant to write, I had to find another audience, which —because I didn’t know how to curate a milieu yet—meant I had to spend the better part of a decade isolated. It was bleak but necessary. Even now, having found you, I need to return to that solitude from time to time. Or else I lose myself.

A distributed apprenticeship

Let me phrase what I’ve been saying in this essay in a slightly different way. What you want to create is a distributed apprenticeship in the art of being you. You want to assemble a set of influences you can observe and imitate, and peers and mentors that can give you feedback on how well you converge with that model of yourself.

The instinct to fit ourselves to our milieu is tricky. It often leads us astray. If not deliberate, we end up internalizing behaviors and values that do not serve us. But it can also, in this way, be a strength: by actively curating your “audience”, as well as what you let into your senses, you can leverage the instinct to conform in your favor. You can create an environment that pulls you in the direction you want to go.

The first step in this process is to locate the right influences—the people and ideas that you want inside of yourself. How to do this in a non-haphazard way is the subject of the next part of this series.

Warmly,

Henrik

This essay is the first of a series. Here is part 2, part 3, and part 4.

This is excellent, looking forward to the rest of the series.

My oldest nephew is now a junior in highschool, and his brother a sophomore. My sister and I were homeschooled, which provided a milieu that, I think, turned us into significantly more thoughtful and interesting people than the standard route of public school would have allowed. But my sister has just sent her boys to public school throughout, which has disappointed me (actually it has made me mad at myself for failing to make the argument more convincingly, or to provide an alternative schooling environment).

I like the way you put it in the final section: you want to create a distributed apprenticeship in the art of being you. There is a vastly larger number of paints and brushes available for someone to learn to draw themselves in a thoughtfully curated personal milieu, than is given in the generic conformity machine of public school. Maybe it's not too late to impart some more color into my nephews' milieu.

This made my night - if not months. Thanks Henrik.