6 lessons I learned working at an art gallery

On agency, doing value-aligned work, and making your job fun

A few days ago, I resigned from my job at the art gallery to write Escaping Flatland full time.

One day I hope to be a good enough writer to put words to how thankful I am to the many people who have helped me reach this point. For now, let me just say that I feel the weight of your care, and I will do my best to honor it.

But before I throw myself into new projects, I want to pause and reflect on the last three and a half years at the gallery—it was an important experience for me, and I want to highlight a few lessons I learned.

(When I began listing, I realized I had learned a lot so I will only cover a small part of it here, mostly lessons around career stuff and agency. I might write what I learned about making art at a later time, if someone is interested (comment!), and about what I learned from the volunteers at the gallery, a group of high agency 70 and 80-year-olds. So much to say!)

Lessons I learned working at an art gallery

The Artist's Garden at Vetheuil, Claude Monet, 1880-81

1. It is possible to turn a mediocre job into a great one

I was the only person who applied for the job at the gallery because it was so shitty: it was basically selling coffee all weekends with lousy pay and no vacations during summers. But in 2021 we had recently moved to Denmark, so I had no professional network and didn’t speak the language, and Rebecka had just been born, and we needed the money—so I couldn’t be picky.

I also felt that the place had, as real estate agents say, “good bones”: it was beautiful, they had 6 exhibition halls, and it was a 25-minute bike ride from home.

For most of my career, I have worked short gigs or at projects that I started—the longest stretch I’ve been employed was, I think, 4 months at a bio lab when I was 19. No, that’s not right; I worked 8 months in a school when I was going down a rabbit hole about education in 2016/17. My working model has been that being employed kind of sucks. But this time, since I knew I couldn’t afford to quit anytime soon with the baby and all, I figured I could try treating it like one of my projects. So instead of selling coffee, I looked into how we could streamline the café and the cash register so that the volunteers who help out at the gallery felt comfortable doing my job, then I made myself a small office where I sat down to analyze the business and figure out how to improve it. You can imagine how popular this was. I had to backtrack for a few months after the board told me to get back to the café. And this was a good lesson for someone who is used to being self-employed: at an institution, you can’t just do what is best, you also have to build trust and coordinate with others so you are on the same page. This, however, doesn’t mean that you should abdicate your judgment and get in line.

I like the approach Sholto Douglas expressed in his interview with Dwarkesh Patel:

If I’m trying to write some code and something isn't working, even if it’s in another part of the code base, I’ll often just go in and fix that thing or at least hack it together to be able to get results. [...] I think that's arguably the most important quality in almost anything. It's just pursuing it to the end of the earth. Whatever you need to do to make it happen, you'll make it happen. [...] I’m just going to vertically solve the entire thing. And that turns out to be remarkably effective.

Ie. you don’t say, “This is my job and that thing is outside my area”—no, if the value you are trying to promote requires you to go outside your role and learn new skills and politick to get the authority to go ahead: then that is your job.

I’m not at the level of Sholto Douglas, but I figured I could at least try. So I made an agreement with my boss, who liked me, that she would let me sit in on the board meetings, and I began mapping out who was who and what they wanted and made sure to talk to all stakeholders when they passed through the gallery, and in 6 months I had a good enough model of what their values and goals were so I could align myself to the mission and make legible to them what I was doing. As my boss learned to trust me, she began to say that my role was “do whatever you think is right,” and eventually, after about a year, “. . . and you work whenever you feel like it.” (It helped that the year I started was the inflection point when the revenue, which had been shrinking or muddling for 5 years, began growing again; this wasn’t all my work, but it made my boss trust me.)

For the last 2.5 years I’ve mostly set my own agenda, and I’ve worked in uneven sprints and bursts, sometimes doing 70-hour weeks (my contract was 20 hours per week), and sometimes staying home for 10 days to write essays. This bursty way of working fits my temperament well, and I’ve genuinely loved this job in a way I didn’t think I’d ever love a job.

A bunch of my friends envied my role. But no one else applied.

2. The best artists I’ve worked with remind me of the best startup founders I know

I’ve worked with . . . ~150 artists from 33 countries. Quite a few of them have been the way artists are typically portrayed: self-centered, hard to work with, a little crazy. These were the amateurs. The best artists I’ve worked with, for example A and B, a husband and wife duo, were not at all like that. Let me give an example.

My boss fundraised and sold a large public sculpture A and B had made earlier this year. The day before we were going to install it, A and B came to the gallery and explained that they had found a better electronic component. Not that the old one was bad—it was the best one they had been able to find when they originally made the sculpture. But the new one was a little bit better. So then they proceeded to dismantle the entire sculpture, get their welding kit, and work for seven hours improving the sculpture. Notice three things:

A and B had already been paid and the buyer was more than happy.

A and B didn’t tell the customer that they had spent 14 man hours improving it; it was just something they did because it was right, nothing they wanted credit for.

A and B have earned enough money from their New York gallerist to retire, but they’d rather use that money to make better art.

It is this kind of attitude that makes someone succeed at their level, as far as I can tell. They are always pushing themselves to the edge, which makes them grow, and they are so selfless and pleasant to work with that you just want to do more stuff with them all the time. And you need that attitude to do anything ambitious: you need support, and funding, and goodwill, and you don’t get that by being disorganized or self-centered. Maybe at the very top of the art world artists can afford to be annoying again, I don’t know.

3. The worst exhibitions take the most work

This is sort of a corollary to the above. When we work with artists like A and B, they answer their emails within the hour and they never complain when we can’t meet an expectation they have and when they come in they work hard and fast and deliver a great exhibition in a few hours. Certain other artists are more like, “oh, I don’t know what I want to do . . .” “can you get me more funding?” “that scratch on the floor makes my art look bad, you need to fix it” “can you build a wall there?” “no that wall wasn’t right after all, can you take it down” and after weeks of this you end up with something mediocre.

I got to run something like an experiment on my capacity to predict which exhibitions would end up great, and which would be a waste of time. It was easy. As soon as someone was slow at answering their email, or complained, or wanted us to be their therapist as they worked through the creative worries, I would tell my boss, “I think we should cancel this.” And my boss—whose strength and weakness is that she thinks the best of people and makes everyone feel held—would say, “Ah, but they are just a bit sloppy with email” “if we just fix this thing it will be fine. . .”

I was right every time; it ended in pain.

And this is quite nice actually: it means it doesn’t take some Tyler Cowen-level taste in talent to figure out who will do good work. I had limited experience with artists. But it turns out that if you are just a bit patient and say, “No, I’m not going to work with anyone who is demanding or confused or slow at answering their email”—then you are basically home.

And when you work like that, when you are patient for the right opportunities, you don’t have to do a lot of work at all. You just go around talking to people until you find a good match...and then the work sort of does itself with little effort. Very convenient!

It is not that I’m some grumpy person who thinks that some people are great and others aren’t, in some predetermined way—I think you can to a large extent decide which kind you want to be. But if someone else isn’t measuring up, I have no idea how to convince them to do so. So I look for people who have already decided.

4. If you care about beauty, you should care about economic growth, too

An art gallery—especially a co-op art gallery with a non-profit board like the one I worked at—is a strange kind of business. The aim is not to earn money but to create beauty and strengthen the community and all of these other hard-to-measure things. Because of this, the gallery attracted people who prefer to think about higher values, rather than stuff like economic growth, which was seen as icky.

I am very much in that direction myself; I found it, for example, almost shameful to turn on paid subscriptions on my blog.

But something that became clear to me at the gallery, and from working with people like A and B who did art at a high level, is that you simply can’t afford to do good stuff if you don’t figure out the funding part.

Our elevator at the gallery, for example, was falling apart, and it would be illegal for us to keep open without one, which meant that we would be unable to do anything if we couldn’t get the money for the elevator—no community, no art, no nothing. My first boss and the board had not realized this, and when I pointed this out, there was a vague feeling that if this happened “the municipality should pay for it because art is so important.”

But the municipality on our island is in bad economic shape, and is considering cutting back on care for the elderly to balance their budget—so, to me, it feels unethical to angle for more money for the arts.1 This is the kind of topic that makes me pound the table in fervor as I talk about it; I have often given this sermon to art students. We have a duty to our values and a duty to our community, and we can’t shy away from that because it feels hard, or because we want to be seen in a certain way, and then expect others to bail us out! We should shoulder our responsibility and figure out a way to make the art (or whatever we value) so attractive and meaningful that people feel good about funding it by becoming members or buying art or coffee or whatever.

If we want to make the world a better place, we can’t just think about the lofty stuff: we have to get our hands dirty and make sure the economic engine works.

5. There are places in the incentive landscape where the incentives are aligned with your values, and your job is to find them

It is not unreasonable to feel icky about the business side of art because the incentives of the market (and the grantmakers . . .) often really do pull in directions that actively threaten the very values that we care about. Yes.

But that is only a rough approximation of the truth.

If you take the time to actually bang your head against reality and figure out how to fund something, you will discover that there are places in the incentive landscape where the incentives (which are really the desires and needs of other human beings) align with your ineffable values. If you want to bring as much of what you have to give into the world, it is our job to figure out where in the incentive landscape that is.

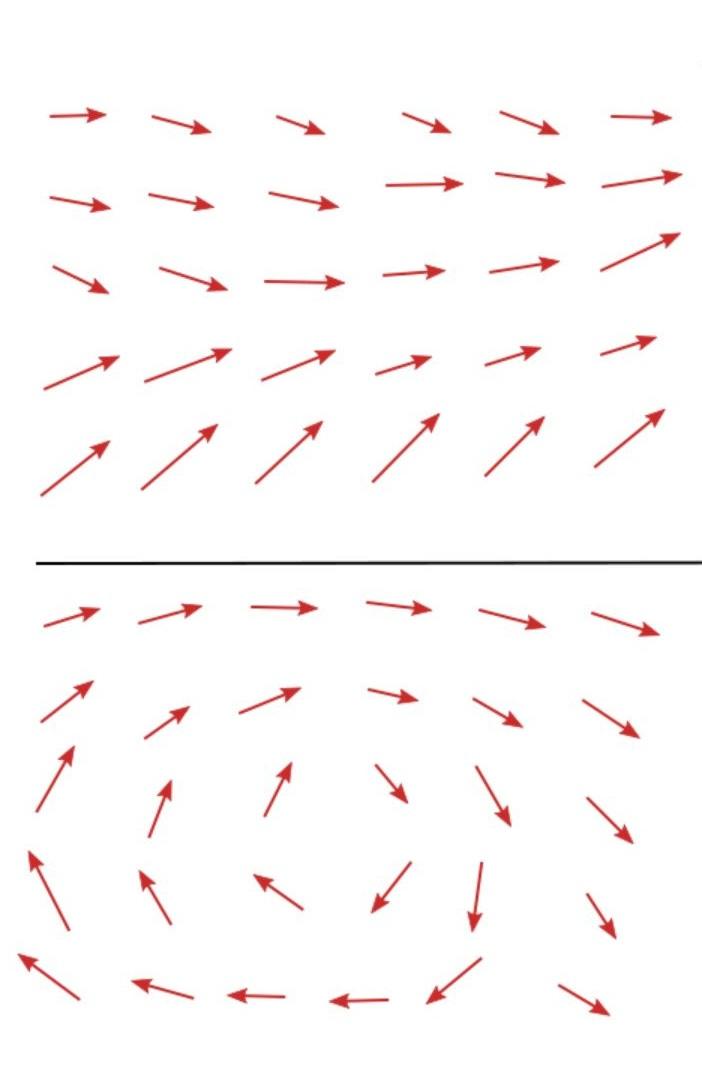

I think of it as two vector fields:

The first vector field is our artistic impulses, and ethics, and curiosity, and so on—all the things that we want to express in our lives (or in our institutions). The other vector field is the market. If you put these vector fields on top of each other and add the vectors together, you find that in most places, the vectors point in different directions, which makes them pull each other off course. Ie. it is harder to make money if you also want to honor your curiosity; and, inversely, it is easy to lose contact with your values if you are also trying to earn money.

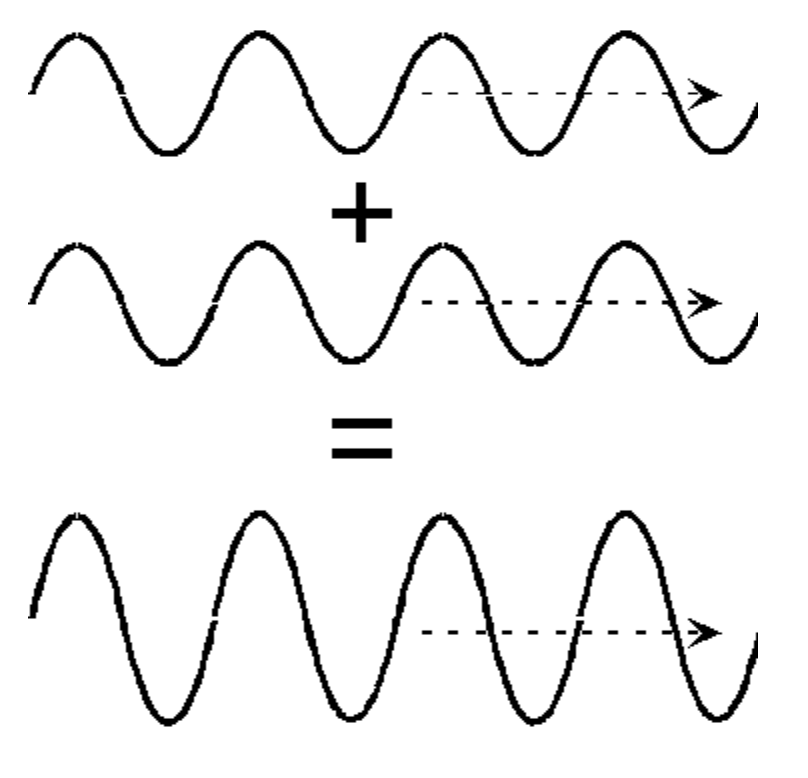

But if you are patient enough, and open-minded enough, and willing to work hard, you can iterate your way to parts where the vectors align. And when that happens, the market forces actually boost the artistic process, as when two waves collide forming a double wave.

What you see in the biographies of great artists, great writers, great anything is that they are good at figuring out where the vectors align. They are able to keep track of their values and be attuned to themselves, and at the same time be cold-headed about how the world works: not shaping themselves to fit the world, but figuring out how to position what they do so that it becomes possible.

6. Most people are not serious

As someone who has been self-employed for most of my life, I have often looked at institutions and felt, “How come they are so slow and bad at their jobs? How hard can it be?” But since I had limited experience, I figured that there was something hard about it that I was too naive to see.

I’m no longer sure I was naive. It was, at the gallery at least, very easy to do much (~3x) better than baseline. For example: when I first came on the board, they would talk about the “three legs” of the gallery: fundraising, workshops, and sales (café, shop, tickets). But when I sneaked away to look at the numbers, two of these “sources of income” were actually cost centers: fundraising and workshops cost us more than we earned.2 No one had looked at our bookkeeping to figure out how we earned our income! Also, they hadn’t factored in building maintenance costs, and when you did that it was clear that the current strategy would bankrupt us in 2-3 years.

These are not hard things to look up; I’m a very amateurish accountant.3 It is surprising how much edge “let me google that” gives you, 26 years after Google was released. (Not to talk about LLMs.) Most people just seem to come up with an answer in their head and then go with that without checking.

To the credit of the board, they did see the problem as soon as I pointed it out, and acted swiftly, and were able to find solutions that I was too inexperienced to find.

When we cut back on workshops and fundraising and focused on the parts that worked, we could do that with more care—running experiments, updating our pricing strategies, automating, streamlining, changing the branding, etc—which, as always when you narrow your focus, made a big difference, and we ended up growing revenue by 311 percent.

Now the expensive maintenance is either done or scheduled to be done, and we’ve built up a war chest, and we’ve set up a strong board, so I feel confident that the place can live on for another ten years—which was the goal I had. I feel ready to get back to my own projects.

In August, King Frederik X, the new Danish King, made an official visit to the gallery during his first tour. Since I’m not in the least a royalist, I was surprised at how sentimental the event made me—seeing him do his weird kingly walk as the preschoolers waved their flags in front of the gallery. I guess it made me feel like I belonged here, and that this country that has given us refuge told us that we were one of them now, that they saw the work we had done to care for this small corner of the whole. It felt like the end of one of the movies of my life, and above my desk as I write this, I keep, as a memento for my years at the gallery, a framed receipt for a sculpture I sold Queen Mary. That was fun.

Since this blog is my only income now, I want to remind you that you can become a paid subscriber if you want to read more or support the production of free essays.

I project that I will be able to earn a normal Danish middle-class income from the blog in a year or two if we can pull through; right now, however, support can make a genuine difference for us. (It is also possible to update your subscription here to support at a higher level if you want.)

This isn’t only a problem with artists. It seems like most people struggle a lot with seeing how making sacrifices in their area might promote the values they believe in better. I was elected to the popular education board for a year and was part of hearings where we were supposed to give feedback on suggestions to reduce the budget for things like the boy scouts and swimming halls and support for homeschoolers. These meetings were a travesty. The board did everything in their power to argue that all cuts were catastrophic, even though it was clear that some were fine while others were in fact very costly and harmful—which meant they provided no useful information to the politicians, who then had to just randomly cut funding. Also, like, when we, as a community have run out of money, shouldn’t we feel the weight and the joy of the weight of figuring out what we can cut so we can save what we value most? Like, just because I happen to be on the popular education board doesn’t mean I can’t conclude that it might be better for us to scale back support for the boy scouts rather than the hospital. When I tried to point this out, the rest of the board looked at me like I was crazy. I remember in particular an old right-wing politician, something of a heavyweight, who turned to me, angry, when I asked if they didn’t feel we had a duty to figure out how to save money? “We have no legal duty to that,” he said. I resigned.

Which is fine if you think that is the best kind of charity you can do, but not if you think you are actually doing it to earn money!

It might sound like I’m being coy and want you to think that I am in fact good at this business stuff. But I’m not. I am, I think, a good writer (and since you probably know me through my writing you might overestimate me). But everything I did at the gallery—curating, branding, renovating, and so on—I had no idea how to do that, and had to learn piece by piece as I ran into problems.

Beautiful. I must hear more about high agency 70 year olds!

I'd love to read more about: the joy of the weight.