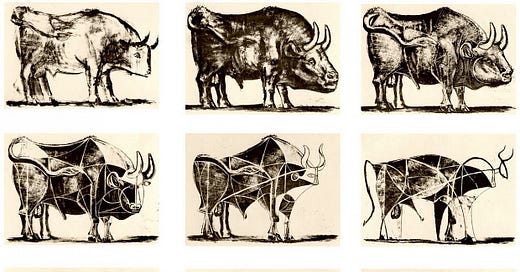

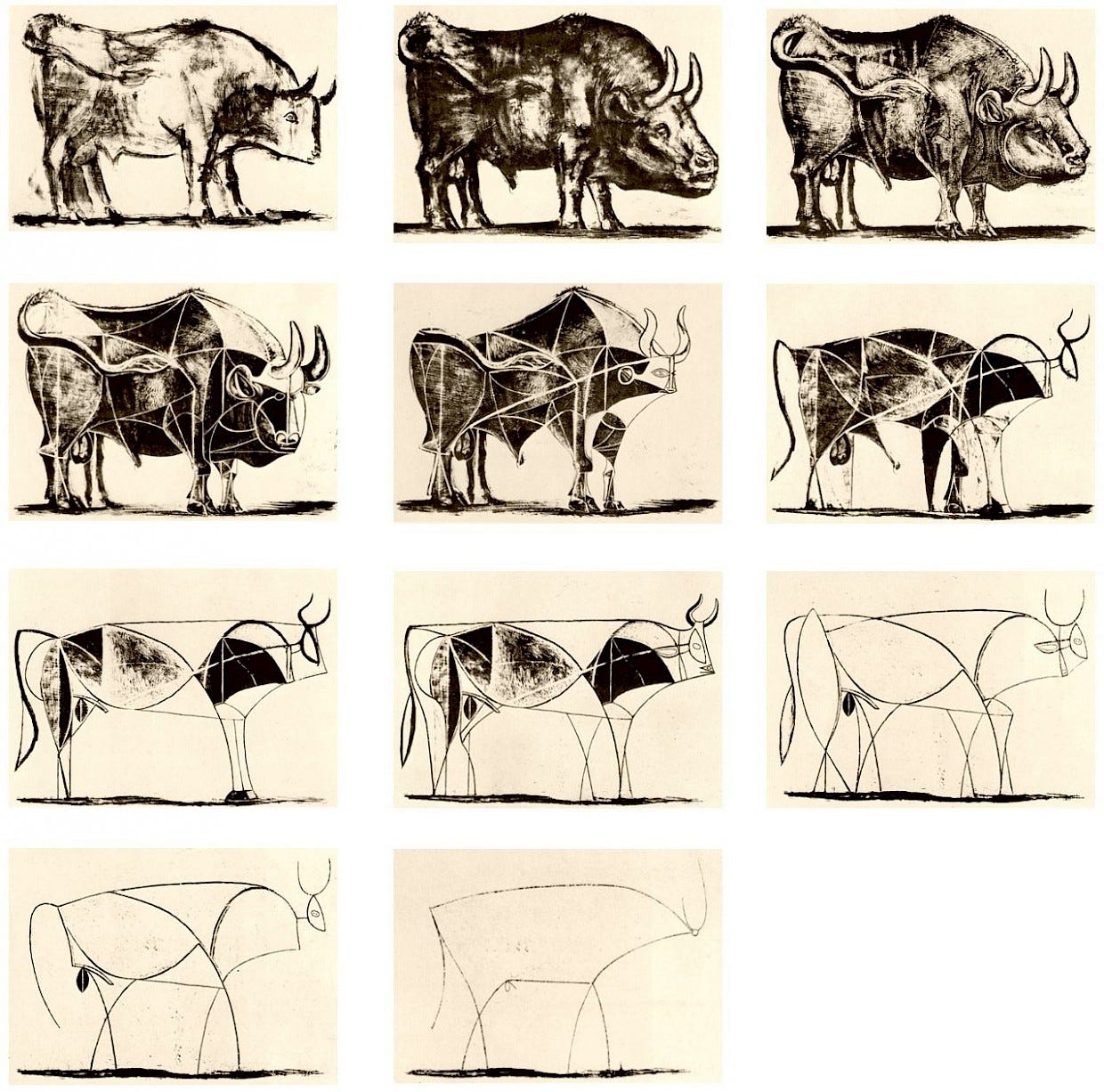

Pablo Picasso, Lithographs from The Bull, 1945-1946

The old dream of having a personal tutor for every child is suddenly within reach with the new generation of AI. Yet as amazing as this is, when I see the excitement among people who proclaim that AI will revolutionize education, I can’t help but think of the story of the bull in Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia.

The story, told by a bitter old lady, is about how the Chilean government in the 1960s tried to establish a model farm in Puntas Arenas. For that purpose the Ministry of Agriculture imported a prize bull to sire new calves:

Oh! the bull! You didn’t know whether to laugh or cry about the bull. The Ministry bought this prize bull in New Zealand [and they flew it] to Santiago, flew it to Punta Arenas, where it was presented, with Lord knows what in the way of speeches, to the so-called model farm. And how long did the bull last? How long before they ate it? Three days!

In a similar vein, I have a feeling we’ll soon be terribly underwhelmed by the changes wrought by AI tutors in the education system.

The core thing lacking at the model farm in Punta Arenas was not a bull; it was the culture necessary to make use of a bull. The reason they needed a bull in the first place was that the workers had eaten the old one.

Yes, people who live in high-growth cultures, and who are motivated to learn, will be able to leverage AI tutors to accelerate their progress. But the rest, lacking access to these cultures, will use the systems to distract themselves and wriggle out of work.

If we want to improve our capacity to help each other grow skilled, the key problem now is figuring out how to scale access to high-growth cultures.

The current state of AI tutors

For a demo of the state of the art of AI tutoring capabilities, watch this video from March 14 where Salman Khan of Khan Academy demonstrates a system built on top of GPT-4.

In the video, Khan uses the AI model as a Socratic tutor. When working on a math problem, he asks the tutor for help and is guided by questions and hints until he’s able to conceptualize the problem in such a way that the solution becomes apparent. He also has open-ended conversations about US history, entropy, and the great wall of China.

GPT-4 occasionally hallucinates answers that are not true. But the models are improving faster than anticipated, and GPT-4 already scores in the top 10 percent on most university exams.

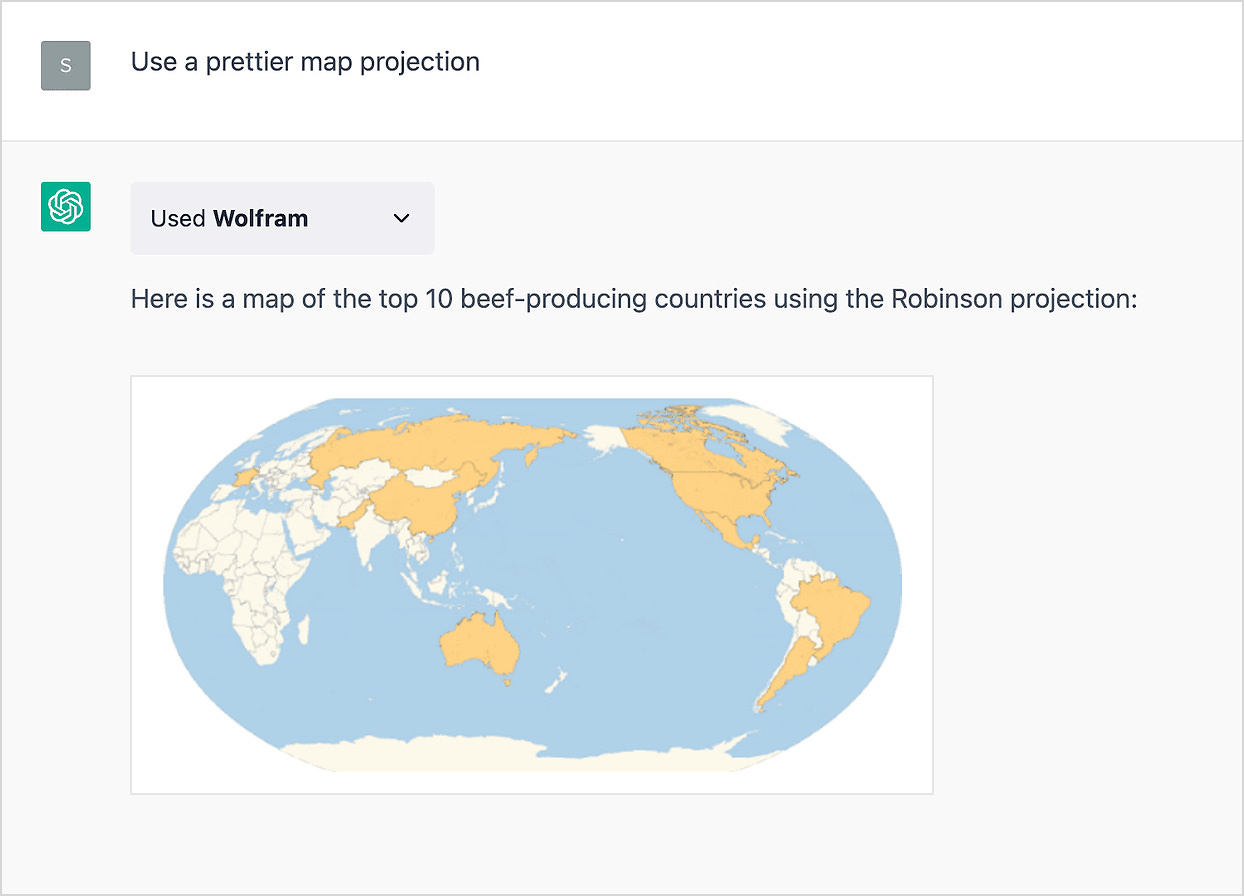

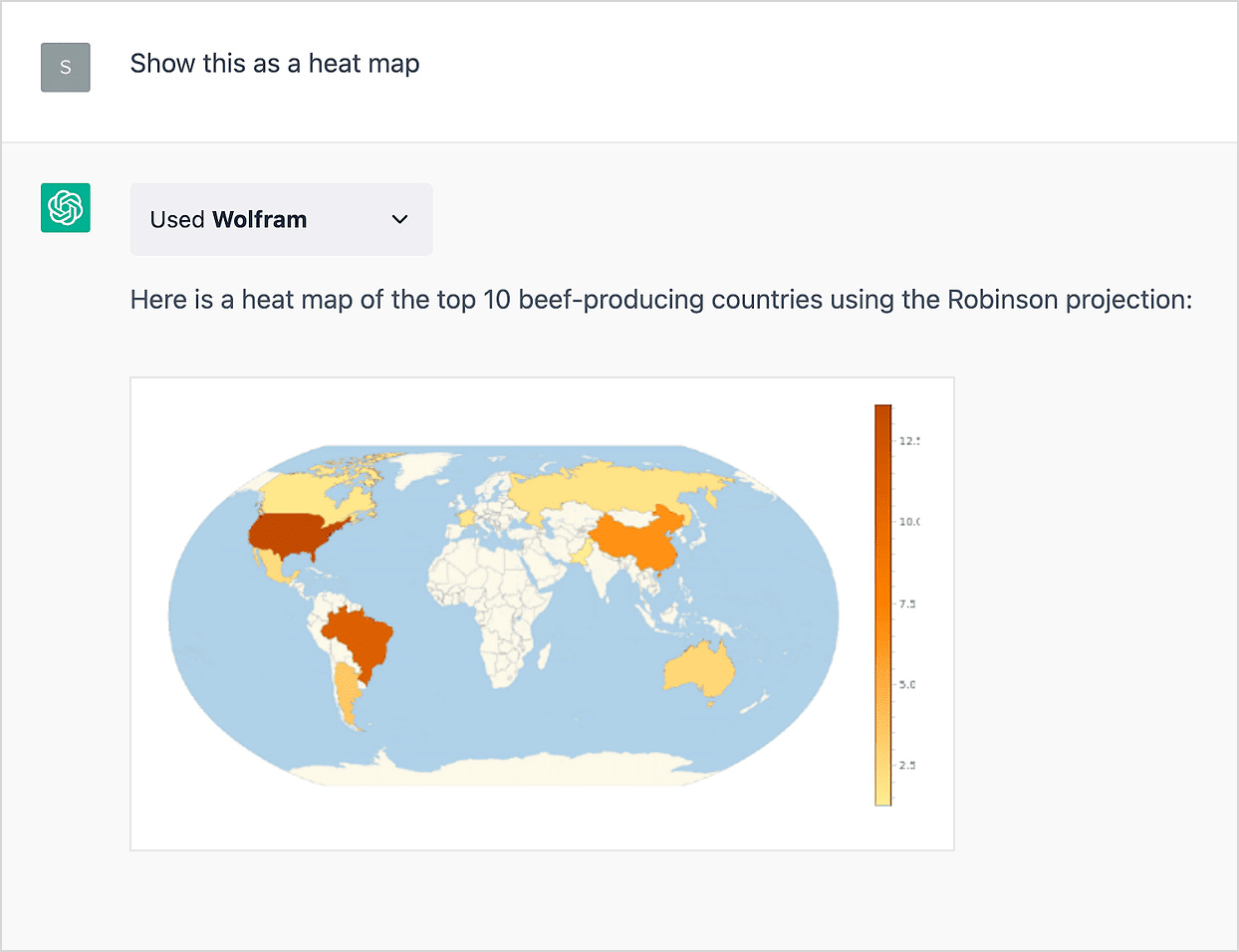

The rate of change is hard to keep up with. On March 23, nine days after Khan demo:ed the tutoring system, OpenAI partnered up with Wolfram and released a plugin that gives GPT-4 the ability to do things like:

This way of fluidly interacting with information, shaping it through dialogue, is immensely powerful. Over the last few days, I’ve been using the system to work on my understanding of graph theory. I ask questions (“what do we know about the relationship between network topology and innovation rate?”) and prompt GPT-4 to use graph theory to answer me. It helps me turn my vague intuitions into more exact terms and figure out the jargon (“assortativity”, “dendrogram”) so that I can search the academic literature. I also ask GPT-4 to write python code to run simulations of various social graph-related scenarios so that I can play around with it and get a visceral feel for the dynamic of networks.

It is not yet a full replacement for a textbook (I use one of those, too) but the speed at which I can navigate and make sense of the material is significantly higher than two weeks ago. And it is entirely open-ended: I use the same tool to become a better gardener.

The potential of AI tutoring systems is related to what educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom called the 2-sigma problem. If you take a median student out of class and give her 1:1 tutoring (Bloom claimed), she will rise two standard deviations (2-sigma) to the top 1 percent of her age group.

More recent research has lowered the effect of tutoring to more realistic numbers, and a meta-analysis found an effect size of 0.36, but this is still a powerful result, enough to take a student from the 50th percentile of achievement to the 64th. From José Rincon’s systematic review of the literature:

Tutoring in general, most likely, does not reach the 2-sigma level that Bloom suggested. [. . .]

But high quality tutors, and high quality software are likely able to reach a 2-sigma improvement and beyond.

If you look at the childhoods of exceptional people, as I did in a recent post, one of the common patterns is that they have received unusual amounts of 1:1 tutoring. ~70 percent of the people I surveyed had been homeschooled, tutored by parents, relatives, governesses, and tutors. It seems likely this is a key reason why they could reach so far in their development.

As J.S. Mill’s father told him upon leaving home, Mill “would discover that others his age [who had not been tutored 1:1] did not know as much as he did. But [. . .] he mustn’t feel proud about that. He’d just been lucky.”

So what will happen now that we can provide everyone with a personal tutor?

The gravitational pull of culture

Making GPT-4 tutor me helps me accelerate my learning, but that is because I’m obsessed with the questions I study. If introduced in schools, I doubt most children would leverage these systems to grow significantly faster. That is not what they are motivated to do; it is not what their culture motivates them to do. (I would wager that PISA test scores for the US will raise by less than 5 percent by 2028, if tutoring systems are introduced in schools.)

The culture we are immersed in shapes our tastes, desires, motivations, beliefs, and so on — shapes it more than you would think if you’ve only interacted with people from a similar cultural background. My first experience being transplanted to another culture was in my late teens when I moved to Malmö and was too naive to figure out that the reason the rent was so cheap was that the house was controlled by a street gang. I had grown up in a village the size of a teacup and was unprepared for how fast children would learn to embrace violence when they grew up in gang culture. You would have ten-year-olds shooting fireworks at people in the street, training themselves to not fear inflicting pain on strangers, and twelve-year-olds showing me their guns in the laundry room. They were mystified by my willingness to read books.

In the US, academic achievement is negatively correlated with the number of televisions in the home, and I suspect this is largely because the number of televisions varies between socio-cultural groups. It is the culture that locks people on unfullfilling life trajectories more than the televisions.

And if we return to my post about people who have made exceptional intellectual or artistic contributions: they didn’t just have tutors, they also grew up in milieus where the people around them valued and pursued those particular types of excellence:

As children, they were integrated with exceptional adults—and were taken seriously by them. When Bertrand Russell, at five years old, refused to believe the earth was round, his grandparents didn’t laugh him off—they called in the vicar of the parish to reason Bertrand out of his misconception.

The adults had high expectations of the children; they assumed they had the capacity to understand complex topics, and therefore invited them into serious conversations and meaningful work, believing them capable of growing competent rapidly.

John von Neumann (the Hungarian physicist who at one time managed the development of the hydrogen bomb and the first digital computer, and as a pastime, at night, invented game theory) was included in the discussions of the management of his father’s bank before reaching school age.

The shape of their motivation was likely influenced by this cultural context and the social roles it elevated.

If you live in a subculture where other things are more valued than intellectual growth (as is true of the vast majority of the youth cultures we exile our teenagers to), there will be limited social incentive to leverage tutoring and other opportunities to grow excellence. It is simply not what will give you status in that culture; it is not what you desire there, what makes you feel safe, what provides you with a stable and socially validated role. Some who end up in these types of cultures in school will push through this, usually because they have cultures that value personal growth at home. But most will be held back by the current of the culture.

Scaling high growth cultures

In other words: the main bottleneck in education, now that tutoring is becoming cheap, is culture design.

Can we figure out ways to scale access to high-growth cultures? Are there ways for more people to grow up in cultures that approximate in richness that J.S. Mill, Pascal, and Bertrand Russel had access to?

It is not a question that has been given serious consideration in the pedagogical literature that influences the design of schools. But there are insights to be mined from anthropology, internet community moderation, lineage traditions in martial arts, small experimental schools, scenes, workplaces, and so on. It is possible to deliberately create high growth cultures, and software makes it easier to scale them. But there are many open questions. (If there is interest, I could do a write-up of my understanding of this design problem.)

Cultures and tutoring systems are complements. The more powerful AI tutors become, the more valuable cultures that support learning will be. (Teaching and tutoring systems, on the other hand, are substitutes, which implies that we can expect teaching to lose value over the coming decade.) There is an opportunity here to direct resources away from things that AI systems can automate, such as teaching, and into the more ambitious project of building better cultural infrastructure.

To be clear: I’m not saying that AI tutors, or other kinds of software, can replace humans. Most of us need the support and community of others to push ourselves to excellence and to find meaning in the projects we pursue. But soon we will be able to spend less precious human time on basic tutoring; instead, the emotional labor we do to support each other can be invested in a more leveraged way.

The education system will be slow to embrace this possibility. But others will.

Warmly,

Henrik

If you want more essays like this to exist, consider liking it. It helps others find it, and it makes me happy. If you have friend who would enjoy my essays, it is really helpful when you share it with them.

"We know that it is possible to deliberately create high growth cultures, and we know that software makes it easier to scale them. But there are many open questions. (If there is interest, I could do a write-up of my understanding of this design problem.)" 🙋♂️

This is very interesting Henrik, I think that a lot of up would like to know more. Screentime is such a big issue in education and I am wandering how this will fit into that conversation.

I could see Simulated Intelligence(SI I refuse to call them AI) doing sort of rote teaching but most of teaching to me is about modeling from the teacher so I have a fair bit of skepticism. The emptiness, the flatness, of the large language models is definitely something that we wouldn't want emulated. I feel like we already have too much of 'seeming alive without actually being alive'.